Prologue

The early hours of that morning announced another day like the ones Lisbon used to know at that time of year: clear, blue and without a trace of any cloud on the horizon. The beginning of summer dawned calm and sunny, the last bohemians were returning home after another night of gathering in Chiado’s cafés and, on the Tagus, flocks of seagulls followed the fishing boats from afar as they left for another journey on the difficult and subtle art of seducing fish.

However, that day, the usual routine of the port of Lisbon was interrupted by an unexpected visitor. At nine o’clock in the morning, after having crossed Cabo da Roca and stopped briefly in Cascais, the yacht Saint-Michel III arrived at its final destination, coming from the Spanish city of Vigo. Of the four men on board, one of them was one of the most popular French writers of his generation. That Wednesday, June 5, 1878, Jules Verne visited the Portuguese capital for the first time.

1. Verne in Lisbon 1878 and 1884: where it is discovered that Jules had an aversion to Portuguese hotels and certain misunderstandings caused by haste are discussed.

In the relationship that Verne established with Portugal, let us begin by briefly evoking the history and itinerary of his two visits to Lisbon, which he noted in detail in his carnets de voyage. For this purpose, we rely on the excellent posts that Frederico Jácome, the greatest contemporary Portuguese Vernian enthusiast, published on his blog, JVernePt, in 2008 and 2014, celebrating the one hundred and thirty years of each of the writer's visits to Portugal.

On his first visit, in 1878, Verne was accompanied by his brother Paul, the son of his editor, Jules Hetzel, and the former French deputy, Raoul Duval (Jácome). Guided by banker Jorge O'Neill (representative of the French shipping company Messageries Maritimes in the Portuguese capital), that morning on 5 June, the writer visited Saint Roch’ Church (Jácome) and, after lunch, met for the first time with his Portuguese editor, David Corazzi (whom we will talk about later).

After having dinner with his traveling companions, with O'Neill and Corazzi at the Grand Hotel Central, one of Lisbon's most renowned restaurants with a magnificent panoramic view over the Tagus River (Leite), Verne watched the zarzuela, La Gallina Ciega (Jácome), at Recreios Whittoyne, a concert hall located in downtown Lisbon (Leite). For no reason that we are aware of, instead of staying in a hotel, Verne spent the night on his yacht.

On the 6th of June, his companions visited Sintra. Verne, however, refused to make the trip to the precious village evoked by Lord Byron in Child Harold Pilgrimage (1812). Not only due to the scorching heat that was felt and that was unbearable, as he himself confirms in a letter written to Hetzel (Margot 58), but also because his attention was totally focused on the Portuguese capital. As stated by Manuel Pinheiro Chagas, in an article published in the newspaper Diário da Manhã, on June 7, 1878, “For him, the novelty was Lisbon” [2] (Margot 60).

The Grand Hotel Central in the 1870s with panoramic view over the Tagus.

And it was to the city, or rather to the areas that had escaped the devastating 1755 earthquake, that Verne devoted his attention: on the second day’s afternoon he visited the Belém Tower and the Jerónimos Monastery.

The epilogue of his first visit took place with a new dinner at the Grand Hotel Central, where he shared the meal with important figures in Portuguese culture and literature of that time, such as the aforementioned Pinheiro Chagas, the writer Ramalho Ortigão (1836-1915) and the artist, caricaturist and illustrator Rafael Bordalo Pinheiro (1846-1905). In the early morning of the 7th of June, at six o’clock in the morning, Verne set sail for Cádiz aboard the Saint-Michel III.

Verne's visit to Lisbon was reported in Portuguese newspapers and also reached Brazil, as it can be read in this article from Jornal do Commercio, of June 29, 1878:

[…] Jules Verne visited the Horas Românticas office, owned by our friend Mr. David Corazzi, who managed, through non-ordinary efforts, to publish in luxurious editions and in Portuguese all the works of that writer, already as popular among us as throughout Europe (Bezerra 66).

The second visit took place six years later. The calendar marked Thursday, May 22, 1884. Verne stopped in Lisbon, in transit to Rome, where he would meet Pope Leo XIII (Jácome). As in 1878, the writer followed the Vigo-Lisbon route on his yacht, where he had dinner that night, and had the opportunity to visit the ships Vasco da Gama and África, both anchored in the port of Lisbon (Jácome).

Panoramic view of 1870s downtown Lisbon. Location of Recreios Whittoyne within the drawn elipse.

Although there are no rumors that a room in Lisbon was more expensive than the price of a suite at the luxurious Parisian hotel Le Meurice, Verne once again declined the appeal of silky Lisbon sheets and, that night, remained faithful to his yacht's bed. On the 23rd, he was awakened at half past five in the morning by the bustle of port activity (Jácome). He dedicated the morning of that day to stroll through Lisbon’s streets, visit the iconic Praça D. Pedro IV (Rossio) and meet David Corazzi.

After having lunch on his yacht and visiting his old friend O'Neill, in the afternoon, at Corazzi's invitation, Verne met Portuguese intellectuals such as Pinheiro Chagas, Ramalho Ortigão and Salomão Saragga, at the Braganza Hotel, headquarters of “Os Vencidos da Vida” (“The Life Losers”) group’s weekly meeting. This group was composed of personalities from the intellectual movement Geração de 70 (Generation of 70), and included, in addition to Ortigão, the historian Oliveira Martins (1845-1894), the poet Guerra Junqueiro (1850-1923) and the writer Eça de Queiroz (1845-1900). It is said that the latter, in The Mandarin (which was offered by Ortigão to Verne), described Beijing and China based on a reading of Les Tribulations d’un Chinois en Chine (Jacome).

The meeting was followed by a dinner, in which Verne was presented for dessert with the Portuguese edition of his works (Compère 414), and a theatrical soirée. At six in the morning on Saturday, 24 May, with a cloudy dawn and with the Tagus River in intense maritime activity, Verne left the Portuguese capital on his yacht at a speed of 9.5 knots, heading for Gibraltar (Jácome).

The writer's second stay was also reported in the press at the time. Among the various articles that were published, let us see what Rafael Bordalo Pinheiro wrote in his satirical newspaper, António Maria, in an article dated 29 May 1884. Regretting the brevity of the French author's stay in Portugal, Bordalo Pinheiro expressed himself in the following ironic terms:

Jules Verne, the illustrious French writer, arrived in Lisbon, dined with David Corazzi and other guests of that editor and left. Only by walking in such a hurry, he was able to make trips to the moon in the time that anyone spends going to Porcalhota [former name of Amadora, 7 kilometers north of Lisbon] to eat rabbit stew. That both he and his brother Paul have a good trip to the Antipodes in an hour and three quarters and if they return to Lisbon, may they stay a little longer for us to show them the garden of Europe planted by the sea.

Braganza Hotel is the building on top. (Credits: C.P. Symends, June 1856)

Perhaps Bordalo Pinheiro was not wrong at all. The brevity that Verne gave to his two visits to Lisbon seems to have, in fact, had some harmful effects. This is mere conjecture, but we are convinced that, due to his meteoric pace of visiting the Portuguese capital, the French author was able to directly influence only one Portuguese author in an attempt to write a purely “Vernian” novel. This is Viscount Sanches de Frias (1845-1922) who, in 1883, published Uma Viagem ao Amazonas (A Trip to the Amazon) (Ferreira 46 6). Who knows, if Verne had stayed longer in Portuguese territory, perhaps the number of Portuguese writers influenced by him would be much greater today.

A few decades later, the Sociedade de Geografia de Lisboa (Lisbon’s Geographical Society) also paid tribute to the hurried way in which Verne passed through the Portuguese capital. In an unusual and not very rigorous gesture, in 1923, the scientific institution decided to celebrate the centenary of the author's birth, anticipating this event by… five years (Jácome).

In addition to these picaresque remarks, it must be said that the writer’s presence in Portugal was remarkable in its time, growing throughout the 20th century and, in the 21st, is still very much alive. What presence are we talking about? More of the presence of Verne’s works in Portugal than the presence of Portugal in Verne's work. Let's start by analyzing the latter.

2. Verne and Portugal: where it is discovered that the most “Portuguese” Vernian work, after all, does not belong to Jules

In Hector Servadac (1877), Verne states that, in general, Portugal and Spain only provide individuals who were not recommended (Compère 395). We cannot comment on Spain, but this motto seems to have been constantly applied to the Portuguese case. In his long literary career, Portugal has never received a great deal of attention from the French writer (Police 434). In none of his works, the Portuguese territory appears as the scene of any relevant episode, except in a vaudeville theater project, whose action takes place in the period of the Restoration War (1640-1668), after the Portuguese independence from the Kingdom of Castile in 1640. This text was first published in 2021 by the Bulletin de la Société Jules Verne, along with other Verne’s unpublished works.

With regard to his most important works, the first direct reference to Portugal appears in Les Enfants du capitaine Grant (1868), 1st part, chapter 15, and, although absolutely hilarious, it was not at all flattering to the Portuguese nation’s historical ego, living mostly from the celebration of its past historical deeds.

Reflecting a commonplace of geographical ignorance that was apparently quite common in 19th century France, that Portugal was an integral part of Spanish kingdom, the hyper-distracted geographer Jacques Paganel reads Camões’s epic poem, Os Lusíadas, in Portuguese thinking that he is learning the Spanish language. When he was alerted to this situation, Paganel simply claims that ”Portuguese and Spanish are so much alike that I made a mistake;”

Such seems to have been this issue’s importance at the time, which was one of the conversation topics in the meeting that Verne held with the Portuguese intelligentsia in his 1878 visit. This what Pinheiro Chagas wrote on the subject, in the Diário da Manhã of June, 7:

He [Verne] could see the lively sympathies that France inspires in us and, in response to an observation regarding the error of many French people who mistake us for the Spaniards or who believe that we are almost Spaniards, he replied that this preconceived idea was disappearing, that in France it was already known that we are a nation full of individuality and strongly attached to its independent existence; he claimed that our section of the Universal Exhibition [of Paris in 1878] was arousing great curiosity and sympathy (Margot 60).

The first Portuguese characters had a fleeting appearance in Verne's work. In Un Capitaine de quinze ans, which he was writing during his first visit to Portugal, in chapter 9, there are the black José António Alves (Kendelé) and his right-hand man, Coimbra, both dedicated to the slave trade in Kasonde, Angola. In La Jangada (1881), chapter 3, Verne mentions a certain Magalhães, an old logger who sells his farm on the banks of the Nanay River to a Brazilian named João Garral. He ended up marrying Yaquita, the daughter of Magalhães, after his death.

In Mirifiques aventures de Maître Antifer (1894), we meet a sailor named Barroso who lives in Loango. With an adventurous temperament, Barroso is a former member of Saouk's gang, who is after Kamylk-Pacha's treasure. After his ship is sunk due to carrying six elephants on board, Saouk promises to reward Barroso (Compère 409), but but he had to wait a long time for compensation because Saouk spent several years in an Edinburgh prison.

The character that Verne developed most consistently (and the one whose name sounds least Portuguese) appears in the first chapters of Le Village aérien (1901). This is Urdax, a fifty-year-old ivory dealer who accompanies John Cort and Max Huber at the beginning of their expedition through the forests of Ubangi. However, in the third chapter, Verne decrees Urdax’s end, when he falls from a tamarind tree, where the expedition members had taken refuge to escape the fury of an elephants’ herd frightened by riffle shots. Urdax is eventually crushed by the pachyderms' powerful paws.

Ironically, the most “Portuguese” work, in which a more significant part of the plot takes place in Portuguese territory, was not written by Verne, but by his son Michel, and published posthumously under his father's name. This is L'Agence Thompson et Co (1908). In this book, between chapters 6 and 15 of the first part, Michel Verne takes his readers through the Azores archipelago, with references to the Faial island (chapter 6) and Ponta Delgada (chapter 9), and also to Madeira archipelago (chapters 13 to 15).

Between chapters 8 and 12, a Portuguese character also intervenes: the noble Dom Higino da Veiga, a passenger on the ship Seamew. Together with his two brothers, Dom Higino steals the crucifix from the church on Terceira Island and a considerable amount of precious stones it contained. The only way the nobleman finds to disguise the theft is to divide the gems between three stomachs: his own and those of his two brothers. The coup ends up being discovered when the Veigas feel ill and their stomachs are washed with boiling water. Subsequently, the three thieves will be handed over to the authorities by the captain of the ship. References to Portuguese landscapes or characters cease at this point, as the Seamew heads towards the Canaries.

If Portugal’s presence in the writer's work is relatively scarce, the same cannot be said of his works’ presence in Portugal. It is a story that is almost completing a century and a half of existence.

3. Verne in Portugal 1874-1973, where it is proved that David Corazzi’s work in the 19th century was the Vernian edition’s mainstay for much of the 20th century

Although initiated in Porto, as it will be seen in this article's Epilogue, the history of Jules Verne's Portuguese edition is closely linked to the city of Lisbon and knows two periods that can be considered distinct. According to the information that we were able to ascertain, Verne's work appears late in Portugal compared to two dates: the beginning of his literary career in France (1863), and his first known Portuguese edition (1867), The Adventures of Captain Hatteras in the North Pole, published in Brazil in fascicle format (Catharina and Guirra 9). However, before we address this issue, a few words are needed about the academic works that have approached it directly or indirectly.

Jules Verne's relationship with Portugal and his publishing history in the country have not yet produced a considerable amount of litterature. The first works on these themes are two communications by Daniel Compère (“Les Portugais et les Brésiliens dans l'oeuvre de Jules Verne”) and Gérard Police (“Jules Verne au Portugal – supplément littéraire aux Voyages dans les mondes connus et inconnus”) presented at the congress La Bretagne, le Portugal, le Brésil - Échanges et rapports, which took place in Rennes between 16 and 19 December 1971. The Proceedings were published in two volumes: the first in 1973 and the second in 1976.

Compère's text deals in a very detailed way with the real and fictional Portuguese in the Vernian universe, ending with an allusion to the writer's visits to Lisbon. Police's paper generally addresses the Vernian edition in Portugal and, as far as we can ascertain, it was the only paper on the subject until the beginning of this century.

More recent works show a growing academic interest in Verne’s presence in Portugal. José António Gomes and Sara Reis da Silva (authors of “Jules Verne en lingua portugesa”) published the first bibliographic research of the author’s Portuguese editions from the 19th century to 2005. Although quite detailed, the authors' research has several gaps, namely because it does not include editions that were not for sale in bookshops such as those of Ediclube (1999) and Editorial RBA (2003).

The largest academic output so far belongs to the researchers María-Pilar Tresaco (University of Zaragoza) and Ana Isabel Moniz (University of Madeira), both belonging to T3AxEL, a research group at the University of Zaragoza with the mission of disseminating the Vernian work. Together, the researchers published “Les archipels Portugais de l'autre Verne” and “Traductions portugaises des Voyages Extraordinaires de Jules Verne (1863-1905)”, both in 2017 and, in 2018, Tresaco alone devoted her attention to the Vernian edition in Brazil (“Les premières éditions brésiliennes des Voyages Extraordinaires de Jules Verne”).

Of the three papers, we are only interested in analyzing some aspects of “Traductions portugaises des Voyages Extraordinaires de Jules Verne (1863-1905)”. Although this paper deals with the Verne’s first Portuguese editions, the bibliographic research we carried out on the same topic does not corroborate some of the results reached by the authors. The factual and historical discrepancies between Moniz and Tresaco's bibliographic research and our own are as follows:

— Moniz and Tresaco indicate that they were only able to find Verne’s translations before 1895 (Moniz and Tresaco 2). Unless the editions subsequent to this date were only registered after 2017 in the National Library of Portugal (one of the sources consulted by the authors), and this is something we cannot prove, all Verne’s works published in Portugal between 1895 and 1905 are registered in PORBASE, the institution's bibliographic database;

— The first translation cataloged by the authors was Cinq semaines en ballon, of which they could not find the first two editions (Moniz and Tresaco 2). However, the work’s second edition, published in 1881, has a record in the database of Bliblioteca João Paulo II (Universidade Católica); [3]

— Robur le Conquérant and Le Chemin de France were not published only in 1890 as the authors claim (Moniz and Tresaco 4). Both works appeared in 1887, as it can be seen from the records we found in Azores Libraries' Collective Catalog [4] and in PORBASE's database; [5]

— Verne's first Portuguese translator was not Mariano Cirilo de Carvalho (Moniz and Tresaco 4), but an advertisement in a newspaper will tell us who was the second.

Despite the merit that must be given to any of these academic works, none of them managed to answer the main question that led us to write this paper: when was a text by Jules Verne published for the first time in Portugal?

Although we thought we were able to properly answer it when this article was first published, we owe ninety percent of the answer to António Joaquim Ferreira (1924-2022), who rigorously traced the historical circumstances of the Vernian's Portuguese publishing enterprise first stages. Ferreira was not an academic, much less an unconditional Jules Verne’s fan. According to what we were able to find out from its former editor, José Manuel Vilela, A.J. Ferreira was an air controller at Lisbon airport by profession and a great admirer of Emilio Salgari’s work.

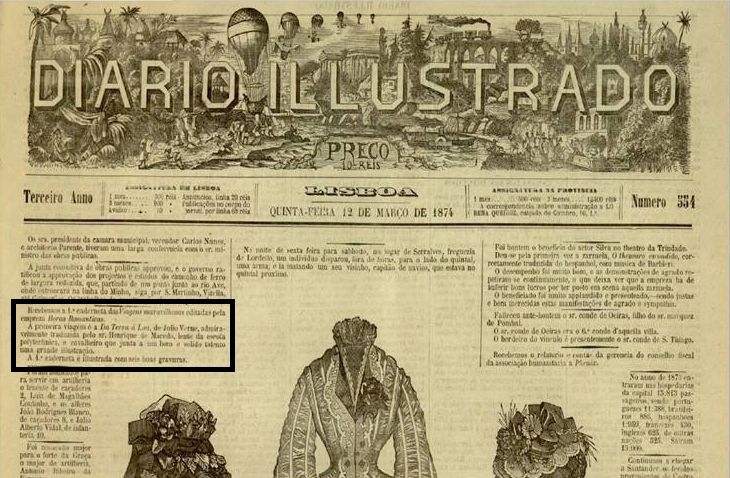

The advertisement in Diário Ilustrado dated March 12, 1874 is marked by the black rectangle. In it can be read: “We received the first booklet of Viagens Maravilhosas edited by the company Horas Românticas. The first voyage is From the Earth to the Moon by Jules Verne, admirably translated by Mr. Henrique de Macedo, professor at the polytechnic school, and a gentleman who combines a good and solid talent with a great illustration. The first booklet comes with six good engravings.”

After retiring, Ferreira visited the National Library of Portugal daily for fifteen consecutive years, carrying out a remarkable research work on children's and youth literature and on Lisbon urban history. He himself donated his work to the National Library of Portugal on the condition that his texts were placed in the instution’s main reading room in order to anyone have easy access to them.

It is in Ferreira's very well-documented text, “How Verne conquered Portugal”, that a part of the answer to the question posed above can be found. The unbearable whims of chance seem to have condemned it to a state of ostracism in typewritten form. This ostracism is not greater because Frederico Jácome published an adaptation of it in his blog JVernePt (2008) and Ariel Pérez Rodriguez translated Jácome’s adaptation into Spanish and published it in the magazine Mundo Verne in the first semester of 2009. Despite this, Ferreira remains an absolutely unknown name for the restricted academic panorama of Portuguese Vernians.

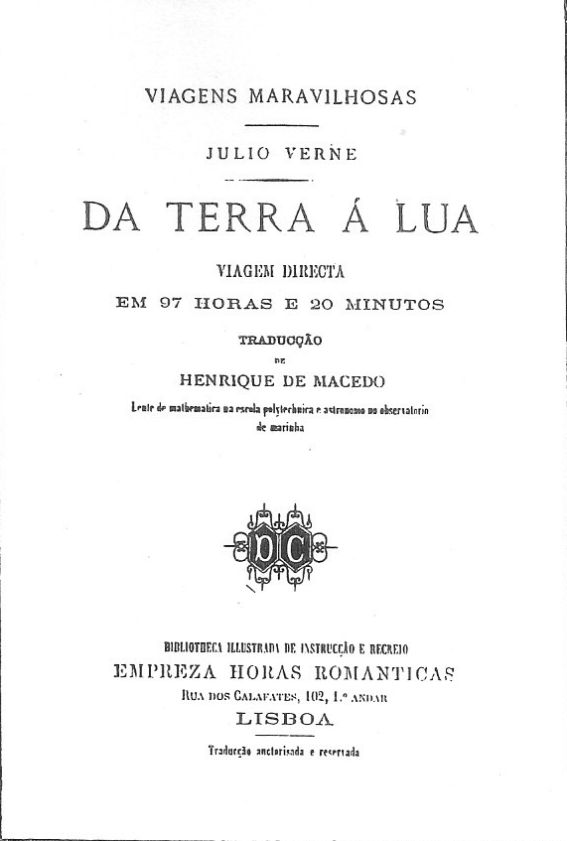

According to Ferreira, in his extensive paper “Como Verne conquistou Portugal” (“How Verne conquered Portugal”), De la terre à la lune was the first work to be published in 1874 in Lisbon by Empreza Horas Românticas, “in fascicles of 32 pages, each with 32 lines” (Ferreira 42 3). The first fascicle’s publication date was March 12, 1874, according to an advertisement in the newspaper Diário Ilustrado (Ferreira 42 3).

|

|

| Cover of Verne’s first Portuguese edition (1874). The publisher's address is still Rua dos Calafates. It was only in 1875 that the company moved to Rua da Atalaya, 40 to 52 (Credit: A. J. Ferreira). | Cover of the first edition of Aventures de trois Russes et de Trois Anglais (1875) (Credit: A.J. Ferreira). |

In the same year, 1874, Autour de La Lune, Le Tour du monde en quatre-vingt jours and Voyages et aventures du capitaine Hatteras would also follow, in this order. In 1875, Cinq semaines en ballon, Aventures de trois Russes et de trois Anglais dans l’Afrique australe and Voyage au centre de la Terre were published.

We did not find bibliographic records of some of these first editions, which, however, does not invalidate the chronology established by Ferreira. As João Almeida Flor claims, in Empreza Horas Românticas’s catalogue,

We very often come up against reprints or second editions of texts previously published in the periodical press in the form of serials but which later on had risen to the material status of books (Flor 135).

Verne's first editions certainly went through this process. Although published in a single and expensive volume (Ferreira 42 3) with a more limited print run, they were also available in the most popular and cheaper fascicle format. This was a commercial strategy adopted by Verne's publisher (Flor 134) and, also, a book industry’s common practice.

According to André Morgado, author of the entry “Editors” in Dicionário de Historiadores Portugueses – Da Academia Real das Ciências ao Final do Estado Novo (Dictionary of Portuguese Historians – From the Royal Academy of Sciences to the end of Estado Novo), in the second half of the 19th century

The fascicles (or notebooks, as they were called at the time) became the privileged way to get the book to more people. Readers bought and collected the fascicles, which periodically arrived at the market, binding them. A simple idea that allowed the publisher to reduce investment; and to the reader, to buy in installments – through agents spread across the country, who sold what was produced.

The fascicles were not just a more comprehensive way of establishing a relationship between author and reader. They were also a way to avoid paying royalties. Although copyright had been regulated in France since the Revolution of 1789, this practice was restricted to French territory and its colonies, and it was almost impossible to prevent the illegal reproduction of books (Bezerra 58). In Portugal, intellectual property was only regulated in the Civil Code of 1867 (Flor 127).

Despite France and Portugal having signed a bilateral treaty (1851) that obliged Portuguese publishers to pay the French authors’ translation rights in Portuguese territory, the works counterfeiting continued for several decades. In Brazil, for instance, although Verne’s publication was being done by Baptiste Garnier’s publishing house, this did not prevent the emergence of other translations commercialized by different publishing companies (Bezerra 65).

The predominance of edition in fascicles also has a lot to do with the Portuguese publishing market’s economic conditions. According to Artur Anselmo,

For economic reasons (difficulty in selling them at a higher price), the editions were of poor quality; luxury books, illustrated or with a good finish (on paper and binding, printed with good quality characters) will only become more common from the 1870s onwards (Anselmo 128).

This situation did not apply only to the Portuguese market. In France, for example, the edition of Verne's works in a single volume was not always carried out in the year of their first appearance. In the Portuguese-speaking workd, Verne’s first book appearance was equally late, happening only in 1873 (Catharina and Guirra 9). The honor of the first edition went to the Brazilian Garnier’s publishing house. These Brazilian editions reached Portugal and were sold by Ernesto Chandron (1840-1885), a French bookseller and publisher based in the city of Porto (Bezerra 69) from whom we found out more information that will be revealed in the Epilogue.

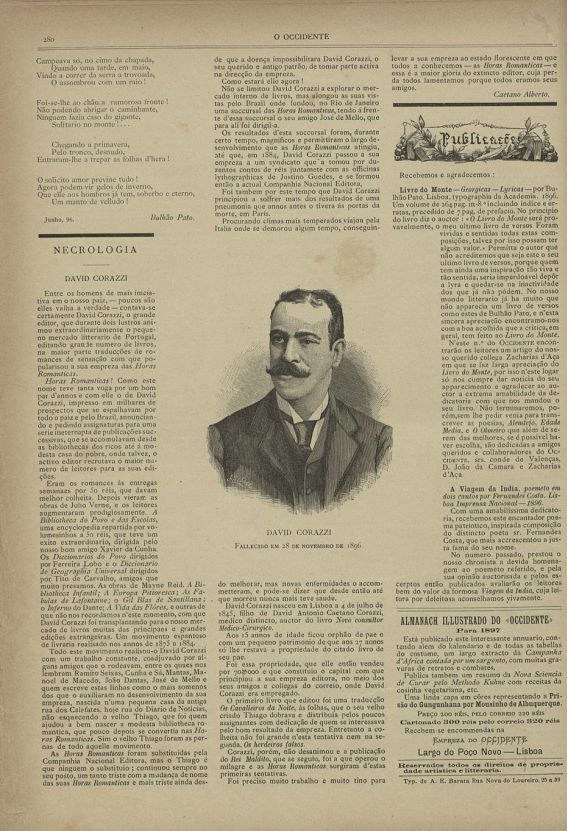

Although Verne's late entry into the Portuguese market is quite perplexing, given the cultural influence that France had on Portugal (Flor 127), his works’ publication was due to the postal services second official at Lisbon’s central station, David Augusto Corazzi (1845-1896).

Orphaned by his father at the age of fifteen, with the sale of the copyright to a book published by his progenitor (a surgeon), Corazzi founded, in 1870, the publishing house Empreza Horas Românticas (The Romantic Hours Company), beginning a worthy work as a publisher and cultural promoter.

The first book published by Corazzi was Les Chevaliers de la Nuit de Ponson du Terrail (1829-1871), followed by El Rey Maldito, by the Spaniard Manuel Fernández y Gonzalez (1821-1888), in 1871. The latter, printed in a new format of eight-page fascicles and engravings, allowed Corazzi the necessary financial relief to boost his publishing house (Domingos 22), and dedicate himself to new projects, such as Biblioteca do Povo e das Escolas (The Library of People and Schools), a collection of cultural and scientific dissemination aimed at a wider audience.

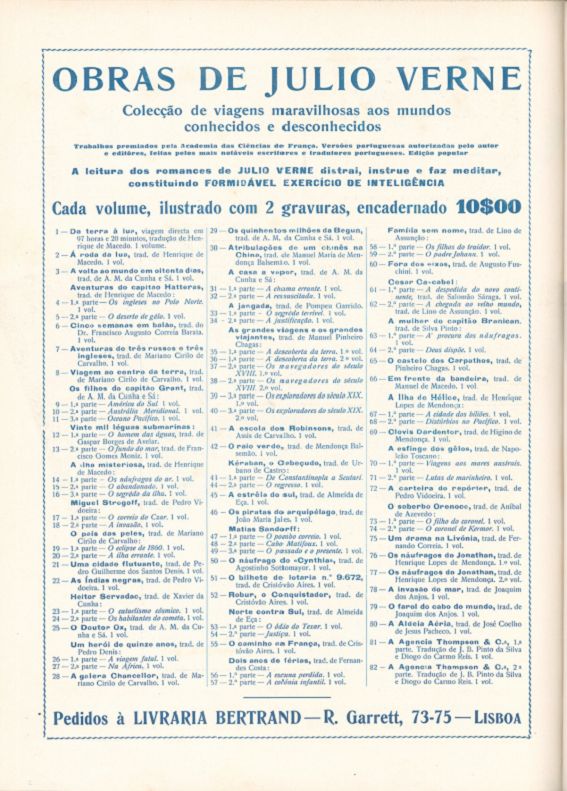

Installed in downtown Lisbon (Rua da Atalaia, numbers 40 to 52) and having its own typography, from 1874 onwards, Verne's Voyages Extradordinaires were successively published by David Corazzi in the collection that he himself called Viagens Maravilhosas aos Mundos Conhecidos e Desconhecidos (Wonderful Travels to Known and Unknown Worlds). In 1886, the collection was renamed Grande Edição Popular das Viagens Maravilhosas aos Mundos Conhecidos e Desconhecidos (Great Popular Edition of Wonderful Voyages to Known and Unknown Worlds) and was published in a slightly smaller and cheaper format than its predecessor “deluxe edition” (Ferreira 43 4).

Giving priority to graphic excellence, Corazzi took the same kind of care with works’ translation. This work was always comissioned to important figures in Portuguese society, coming from different professional backgrounds (see Attachment 1 where we present a brief biography of almost all of Verne's first Portuguese translators): writers (Manuel Pinheiro Chagas and A.M. da Cunha e Sá), military (Fernandes Costa and Almeida D'Eça), doctors (Fernando Correia and Xavier da Cunha) or painters (Manuel Macedo and Higino Mendonça).

The publishing of Verne's works followed the various changes in the commercial name that the publishing house underwent: first Empreza Horas Românticas (1870-1883) gave way to Casa Editora David Corazzi (David Corazzi’s Publishing House) (1884-1888). Later, already in partnership with the typographer Justino Guedes (1852-1924), it changed its name to Companhia Nacional Editora (National Publishing Company) (1890-1902).

From 1903, Companhia Nacional Editora ceased to be Companhia Nacional and started to appear simply with a name that did not presage that so many romantic hours: A Editora (The Publishing House). And, in fact, from 1905 onwards, the company began to experience setbacks of different kinds. Seeing a decrease in quantity and quality in its editorial volume (Domingos 91), the Editora would definitively end its activity in 1912.

David Corazzi’s obituary. Revista Occidente, December 15, 1896.

David Corazzi's life also met with several setbacks, not even reaching the 20th century. In 1890, he was forced to cease his professional activity due to declining health. He would die on November 26, 1896, due to heart complications.

His early departure from the publishing business was a severe blow to the Vernian edition in Portugal. This statement can be explained by comparing some numbers. From 1876 to 1892, apart from Verne’s works that had been published in the period prior to the first date, David Corazzi published the Voyages Extraordinaires in the same year they appeared in France or, at most, the following year, with only two exceptions: Deux ans de vacances and Les Premiers explorateurs. The last work to see the light of day on Portuguese soil within this temporal schedule was Mistress Branican (1891), published in 1891 and 1892.

In the period of Justino Guedes’s management, the situation drastically changed and the Vernian edition became much slower. Here is what we found in our bibliographic research: Le Château des Carpathes (1892) had the first Portuguese edition only in 1894, Claudius Bombarnac (1892) in 1900, l'Ile à hélice (1895) in 1898/1899, Face au drapeau (1896) in 1898, Clovis Dardentor (1896) in 1899, Le Sphinx des glaces (1897) in 1899, Le Superbe Orénoque (1898) in 1903, Un drame en Livonie (1904) in 1911, L'Invasion de la mer (1905) ) in 1912, Le Phare du bout du monde (1905) in 1912 and Les Naufragés du Jonathan (1909) in 1911.

Le Village aérien (1901) and L’Agence Thompson and Co (1908) would be published much later, respectively in 1937 and 1938, but already by other companies that marked an important period in the 20th century’s history of the Portuguese and Brazilian book edition. In order to better understand the following chapters of Verne's Portuguese edition it is necessary to mention these two names: Francisco Alves de Oliveira (1848-1917) and Júlio Monteiro Aillaud (1858-1927). It was on the basis of their transnational corporate mergers undertaken in the 1910s that Verne continued to be a prestigious author in Portugal throughout most of the twentieth century.

Francisco Alves, although born in Portugal, was a Portuguese-Brazilian bookseller based in Rio de Janeiro since 1863, where he went to work at Livraria Clássica (The Classical Bookshop), founded by his uncle, Nicolau António Alves, in 1854 (Bragança 231). Aiming to work on his own, it was only in 1897 that Alves managed to get his project done: in that year he completely took over the direction of Livraria Clássica, which, from 1903 onwards, would be known simply as Livraria Francisco Alves (Francisco Alves Bookshop).

Owning the largest publishing house and bookshop in Brazil at the beginning of the 20th century, Francisco Alves decided to expand his business to Portugal in 1907, acquiring a part of Aillaud’s publishing house (bookshop and typography). In 1910, Alves and Aillaud bought the centenary Livraria Bertrand (Bertrand Bookshop) and even before that, in 1908, Alves had become the major shareholder of A Editora (Bragança 238), completing its total acquisition in 1912. With these business moves, Aillaud and Alves became holders of Verne's publishing rights in Portugal and Brazil.

Owning the largest publishing house and bookshop in Brazil at the beginning of the 20th century, Francisco Alves decided to expand his business to Portugal in 1907, acquiring a part of Aillaud’s publishing house (bookshop and typography). In 1910, Alves and Aillaud bought the centenary Livraria Bertrand (Bertrand Bookshop) and even before that, in 1908, Alves had become the major shareholder of A Editora (Bragança 238), completing its total acquisition in 1912. With these business moves, Aillaud and Alves became holders of Verne's publishing rights in Portugal and Brazil.

In Portugal, the writer would be published by the Aillaud and Bertrand Company between 1926 and 1934. However, new business moves took place that interrupted this editorial project: after Aillaud's death in 1927, his daughter, Germaine, associated the company with Livraria Lellos in the city of Porto (Bragança 240). In 1933, Bertrand became a limited company (Morgado), to be bought in 1942 by the French bookseller, Marcel Didier (Ferreira 45 3).

Verne's works advertisiment. 82 titles published by Bertrand. Revista Illustração (December 16, 1938).

From 1934 until 1974, Verne was published almost exclusively by Bertrand. However, these new editions owe everything to the editorial work done by David Corazzi in the 19th century. Both Aillaud and Bertrand, first, and Bertrand, later, kept the designation of Great Popular Edition of the Wonderful Voyages to Known and Unknown Worlds and their respective numbering (eighty-two volumes published between 1874 and 1938).

In 1956, there was a complete works' re-edition, in which the Portuguese spelling was updated, in accordance with the Orthographic Agreement of 1945. The last major reprint of Verne's work at Bertrand began in 1967 (Ferreira 45 3) and ended in the early 1980s. Corazzi's edition, once again, continued to be the reference edition.

This was the last major collection of Verne's works by any Portuguese publisher or publishing group. The most recent collection of his works in Portugal, already published in the 21st century, (as we will see in the last section of this article) was not of Portuguese origin, nor was it ever available in bookshops.

However, back to the 20th century: in the 1960s new rising publishing projects released some Verne’s titles. Positive points: these are editions that feature new translations. Negative points: the strategic tendency to publish only the author's best-known titles. The only exception to this rule was the release of a work hitherto unpublished in Portugal, Le Maître du monde, by Europa-América in 1960.

The editorial companies that published Verne’s in the 1960s are the following: Europa-América (De la Terre à la Lune, 1960; Les Aventures du capitaine Hatteras, 1960; L'Île mystérieuse, 1960; Le Rayon vert, 1960; Robur le conquérant, 1960; Une Ville flottante, 1970) and Aster (Autour de la Lune, 1960; De la Terre à la Lune, 1965; Le Tour du monde en quatre-vingt jours, 1966).

Despite these new editions, Bertrand’s “hegemony” remained intact. It was not until 1974 that new companies would publish the French author. But not even these risked much in terms of commercial and editorial strategy until today.

4. Verne in Portugal 1974-2021: where the conformism of the Portuguese publishing market with regard to the Vernian edition can be seen

This chronological period can be portrayed in a more telegraphic way for two reasons: first, because of its smaller temporal dimension compared to the period 1874-1973, but, above all, because of the Portuguese publishing market’s clear one-dimensionality criteria with regard to Verne’s works.

The year 1974 brought not only the Portuguese political regime’s democratization, but also some changes to the Vernian edition in Portugal. This democratization had positive aspects, although not very innovative, given the position that Jules Verne still holds in the world literary scene.

Bertrand continued to republish the writer's work, presenting only a single hitherto unpublished title (La Chasse au metéore, 1978), but gradually eclipsed the market to make way for new publishing companies in the following three decades.

In the second half of the 1970s, as well as in the 1980s and 1990s, the writer’s edition was carried out by the aforementioned Europa-América, but also by Círculo de Leitores, Livros do Brasil, Amigos do Livro and other editorial projects of greater or lesser relevance that existed in these years. However, the commercial strategy followed by all these publishers was always guided by an overly prudish and conservative spirit: once again, all of them published only the best-known titles to the public.

The only and honorable exception to this scenario is that of Edições António Ramos. Between 1978 and 1981, this company published for the first time in Portugal the following titles: L'Étonnante aventure de la Mission Barsac (1978), Le Secret de Wilhelm Storitz (1978), Le Pilote du Danube (1980) or P'tit-Bonhomme (1981) ), and Hier et Demain (1978).

Another praiseworthy exception: the works initially written by Michel Verne and recovered by Société Jules Verne were published in the early 2000s by the now extinct Editorial Notícias: La Chasse au metéore (1999), Le Secret de Wilhelm Storitz (1999), Le Volcan d'or (2000), Un prêtre en 1839 (2001) and Le Phare du bout du monde (2005). Regarding unpublished works, we should also mention the two exceptions to Editorial Notícias: L'Oncle Robinson (1991) published by Livros do Brasil one year after its original edition and the resurgence of Verne at Bertrand with Paris au XXe siècle (1994) in 1995.

The 21st century’s first decade, and the celebration of Verne’s death centenary (2005), spurred a growth of interest in his work in Portugal: two daily newspapers, Correio da Manhã (2002-2003) and Público (2005) published a partial collection of his works.

The largest edition of the Corpus Verniano, however, did not belong to a Portuguese publishing house, but to the Spanish Editorial RBA, which, in 2003, released a collection of sixty-seven volumes updating the “Corazzi method” of the 1870s: weekly distribution of a volume (instead of fascicles) in stationery stores and newspaper kiosks. Unfortunately, this collection was never made available in bookshops, which prevented its wider dissemination to a larger audience.

There are very positive factors in Editorial RBA’s collection, such as the possibility for readers to get in touch with lesser-known Verne’s works (such as Claudius Bombarnac or Le Chancellor). However, the most negative aspect is the systematic use of 19th century translations without any proofreading carried out by contemporary translators. Although it is only available in second-hand booksellers, RBA’s edition remains the most complete gateway to Jules Verne's work released in Portugal in the 21st century.

The 2010-2020s, and early 2020s, pursued the same kind of one-dimensional trade strategy. Verne’s work returned, so to speak, to its 20th century’s “mother house”, that is, to Bertrand, who has republished his most popular works (with new or revised translations), through the 11x17 editorial, which is part of its business group.

The same strategy has been followed by other publishers, larger or smaller, without being possible to have direct access in bookshops to Verne’s lesser-known works. To obtain them, public libraries and second-hand booksellers remain the best resources for the author's most avid readers.

Finally, and still according to our bibliographic research, given the number of editions it has seen in almost one hundred and fifty years, Le Tour du monde en quatre-vingt jours continues to be Verne's most popular work in Portugal. However, we are still waiting for the Portuguese edition of his complete works. We just sincerely hope that this Lusitânia Verne’s editorial “round the world”, if it happens, will not take eighty years to be completed.

Works cited

Anselmo, António. Estudos de História do Livro. Guimarães, 1997.

Bezerra, Valéria. “Le Tour du Monde” das obras de Jules Verne: Uma análise da atuação internacional dos editores Pierre-Jules Hetzel e Baptiste-Louis Garner. Alea: Estudos Neolatinos, vol. 24/1, 52-76.

Bragança, Aníbal. “O Editor de Livros e a Promoção da Cultura Lusófona: a trajectória de Francisco Alves”. In Bragança, A. (Ed.) Rei do Livro – Francisco Alves na história do livro e da leitura no Brasil. Edusp, 2016, 227-243.

Catarina, Pedro and Guirra, Edmar. “Jules Verne na Imprensa Brasileira no Século XIX”. Pensares em Revista, nº4, 2014, 5-25.

Compère, Daniel. “Les Portugais et les Brésiliens dans l’oeuvre de Jules Verne”. In Massa, J.M., La Bretagne, le Portugal, le Brésil – Échanges et rapports, Volume 1. Univerisité de Haute Bretagne, 1973, 395-415.

Domingos, Manuela. Estudos de Sociologia da Cultura: Livros e Leitores do Século XIX. Instituto Português do Ensino à Distância, 1985.

Ferreira, António Joaquim. “Como Jules Verne Conquistou Portugal”. Nº13 – Informações e Estudos sobre Jornais Infantis, Literatura Popular e Histórias aos Quadradinhos 42-46, 1994.

---. “¿Como Verne conquistó Portugal?. Mundo Verne, Nºs 9-10, 18-20, 2009.

Flor, João Almeida. “Publishing translated literature in late 19th century Portugal: the case of David Corazzi’s catalogue (1906)”. In Seruya T., D’Hulst L. e Moniz, M.L., Translation in Anthologies and Collections (19th and 20th Centuries). John Benjamins Publishing Company, 2013, 123-136.

Gomes, José António and Silva, Sara Reis. “Jules Verne en Língua Portuguesa”. In Roig Rechou, B.A. (Ed.) Hans Christian Andersen, Jules Verne e El Qujote na literatura infantil e xuvenil do marco ibérico. Edicións Xerais de Galicia, 2005, 151-165.;-p:

Jácome, Frederico. “130º Aniversário da visita a Portugal”. JVernePt, 5 June 2008, jvernept.blogspot.com/2008/06/130-aniversrio-da-visita-portugal.html.;-p:

---. “Artigo – Como Jules Verne conquistou Portugal. JVernePt, 14 August 2008, jvernept.blogspot.com/2008/08/artigo-como-jules-verne-conquistou.html.;-p:

---. “Há 130 anos J. Verne voltou a Portugal”. JVernePt, 22 May 2014, jvenept.blogspot.com/2014/05/ha-130-anos-j-verne-voltou-portugal.html.;-p:

Leite, José. “Livraria Bertrand”. Restos de Colecção, 31 December 2010, restosdecoleccao.blogspot.com/2010/12/livraria-bertrand.html.;-p:

---. “Grand Hotel Central em Lisboa”. Restos de Colecção, 1 September 2016, restosdecoleccao.blogspot.com/2016/09/grand-hotel-central-em-lisboa.html.;-p:

---. “Recreios Whittoyne”. Restos de Colecção, 28 December 2017, restosdecoleccao.blogspot.com/2017/12/recreios-whittoyne.html.;-p:

---. “Braganza Hotel”. Restos de Colecção, 4 January 2018, restosdecoleccao.blogspot.com/2018/01/braganza-hotel.html.;-p:

Margot, Jean-Michel. “JV à Lisbonne les 5 et 6 Juin 1878”. Bulletin de la Société Jules Verne, nº58 – 2e trimestre 1981, 59-61.;-p:

Moniz, Ana Isabel and Tresaco, Maria-Pílar. “Traductions portugaises des Voyages extraordinaires de Jules Verne (1863-1905) ”. Carnets – Revue électronique d’études françaises de l’APEF, Deuxième série – 9, 2017, 1-10.;-p:

Morgado, André. “Editores”. Dicionário de Historiadores Portugueses – Da Academia Real das Ciências ao Final do Estado Novo, 2017, dichp.bnportugal.gov.pt/tematicas/tematicas_editores.htm.;

Police, Gérard. “Jules Verne au Portugal : supplément littéraire aux voyages dans les mondes connus et inconnus”. In Massa, J.M., La Bretagne, le Portugal, le Brésil – Échanges et rapports, Volume 2. Univerisité de Haute Bretagne, 1976, 433-441.

Tresaco, María-Pilar and Moniz, Ana Isabel. “Les archipels Portugais de l’autre Verne”. In Tresaco, María-Pilar, Cadena, Maria Lourdes e Claver (Coord.), Otro Viaje Extradordinario. Prensas de la Universidad de Zaragoza, 2017, 211-224.

---. “Les premières éditions brésiliennes des Voyages extraordinaires de Jules Verne”. In Dialogues France-Brésil: Circulations, représentations, imaginaires, Eden Viana Martin, NejmaKermele et al. (dir.). Presses de l'Université de Pau et des pays de l'Adour, 2017, 225-241.

Notes

- Lusitânia was an ancient Iberian Roman province located where modern Portugal and part of western Spain. Lusitânia was and is often used as an alternative name for Portugal. ^

- The translation of all in-text citations, Portuguese book titles and company names are my responsability. ^

- catalogo.bibliotecas.ucp.pt/cgi-bin/koha/opac-detail.pl?biblionumber=433750. ^

- ccbibliotecas.azores.gov.pt/cgi-bin/koha/opac-detail.pl?biblionumber=440688&query_desc=kw%2Cwrdl%3A%20verne%20O%20caminho%20da%20Fran%C3%A7a ^

- porbase.bnportugal.gov.pt/ipac20/ipac.jsp?session=1654610L1U5T5.94450&profile=porbase&source=~!bnp&view=subscriptionsummary&uri=full=3100024~!3114294~!0&ri=14&aspect=subtab11&menu=search&ipp=20&spp=20&staffonly=&term=robur+o+conquistador&index=.GW&uindex=&aspect=subtab11&menu=search&ri=14. ^

Attachment 1 – Short biography of Jules Verne’s first Portuguese translators

Cristovão de Magalhães Sepúlveda Aires (1853-1930) — Lieutenant Colonel of Cavalry, Professor of the Army School, deputy; author, among others, of História Orgânica e Política do Exército Português (Organic and Political History of the Portuguese Army) and Fernão Mendes Pinto e o Japão (Fernão Mendes Pinto and Japan) (1906).

Joaquim dos Anjos (1856-1918) — Journalist; author of Manual do Typógrapho (The Typographer’s Handbook) (1886), director of Grande Elias: Semanário Ilustrado, Literário e Teatral (1903-1905).

Tomás Lino de Assunção (1844-1902) — Civil engineer, employee of the Ministry of Public Works and playwright; author of Os Lázaros (1899) and Eva (1899); he wrote for the magazines Brasil-Portugal: Revista Quinzenal Ilustrada, Serões: revista semanal ilustrada e and the newspaper O Dia.

Gaspar Borges de Avellar (1844-1889) — Writer and journalist; he wrote for Porto’s newspaper Diário da Tarde.

Aníbal Lúcio de Azevedo (1876-1952) — Mining engineer, director of the Portuguese Mint and Member of Parliament.

Manuel Maria de Mendonça Pinto Balsemão (1836-1907) — Translator.

Francisco Augusto Correia Barata (1847-1950) — Full Professor of Philosophy at the University of Coimbra; author, among others, of As Raças Históricas da Península Ibérica (The Historical Races of Iberian Peninsula) (1873) e Origens Antropológicas da Europa (Anthropological Origins of Europe) (S/D).

Mariano Cirilo de Carvalho (1836-1905) — Politician and journalist; he wrote for the newspaper Gazeta de Portugal (1864-1867) and founded the newspapers Notícias, Novidades (1885), Correio Português e Diário Popular.

Artur Urbano Monteiro de Castro (1850-1902) — Writer and journalist; director of the newspapers Correio da Manhã, Diário da Manhã and A Tarde; author, among others, of Rimas Simples (Simple Rhymes) (1895) e de Na Aldeia: Comédia em Um Acto (In the Village: Comedy in One Act) (1896).

Manuel Pinheiro Chagas (1842-1895) — Journalist, writer and politician; author, among others, of Poema da Mocidade (The Poem of Youth) (1864).

José Fernandes Costa (1848-1920) — Artillery General and poet; founder and sole editor of Almanach Bertrand between 1900 and 1920; author of O Eterno Feminino: Realismos e Evocações (The Eternal Feminine: Realism and Evocations) (1910).

Fernando da Silva Correia (1893-1966) — Hygienist, professor and writer; author, among others of Leonor de Lencastre: Tragédia de uma Grande Alma (Leonor de Lencastre: Tragedy of a Great Soul) (1932) and Vida Errada: O Romance de Coimbra (Wrong Life: Coimbra’s Romance).

Henrique de Macedo Pereira Coutinho (1843-1910) — Full Professor of Mathematics at the Polytechnic School of Lisbon; Minister of Navy and Overseas and founding member of the Portuguese Geographical Society.

Xavier da Cunha (1840-1920) — Doctor, writer and poet; director of the Portguese National Library between 1902 and 1911; he wrote for the newspaper Gazeta de Portugal; author, among others, of A Bíblia dos Bibliófilos (The Bibliophiles Bible) (1911).

Pedro Guilherme dos Santos Diniz (1829?-1896) — Poet and writer; author of the poem Animal Voices and, under the pseudonym of Amaro Mendes Gaveta, of As Folhas Caídas Apanhadas a Dente e Publicadas em Nome da Moralidade (The Fallen Leaves Caught with Teeth and Published in the Name of Morality) (1854), a satire on the work of Almeida Garrett, Folhas Caídas (The Fallen Leaves).

Vicente Almeida d'Eça (1852-1929) — Military, historian and oceanographer; author, among others, of Luís de Camões Marinheiro (The Sailor Luís de Camões) (1880) and O Infante D. Henrique e a Arte de Navegar dos Portugueses (The Infante D. Henrique and the Art of Sailing of the Portuguese) (1894).

Augusto Maria Fuschini (1843-1911) — Civil engineer, painter and watercolorist; author, among others, of O Presente e o Futuro de Portugal (Portugal’s Present and Future) (1899) and A Arquitectura Religiosa na Idade Média (Religious Architecture in the Middle Ages) (1904).

João Maria Jalles (?-?) — Military, Full Professor of Artillery and writer; author of the volumes of Geology, Mineraology, Gravity, Trigonometry and Mechanics in David Corazzi’s collection, Biblioteca do Povo e das Escolas (Library of the People and Schools).

Manuel Maria de Macedo (1839-1915) — Painter, set designer and illustrator; co-founder and artistic director of the magazine Occidente (1878) and author of Restauração de Quadros e Gravuras (Restoration of Paintings and Engravings) (1885), the first book on painting restoration and conservation published in Portugal.

António Higino de Magalhães Mendonça (18??-1920) — Painter, journalist and art critic; he wrote for the newspaper Novidades.

Henrique Lopes de Mendonça (1856-1931) — Military, historian and naval archaeologist; author, among others, of Sangue Português: Contos de Outro Tempo (Portuguese Blood: Tales of Another Time) (1920) and Vasco da Gama na História Universal (Vasco da Gama in Universal History) (1925).

José Coelho de Jesus Pacheco (1894-1951) — Military, entrepreneur and poet; he wrote for the magazines Renascença (1914) and Correio Ilustrado (1916).

António José da Silva Pinto (1848-1911) — Writer and playright; author, among others, of Contos Fantásticos (Fantastic Tales) (1875) and O Padre Gabriel, Drama Original em Três Actos (Father Gabriel, Original Drama in Three Acts) (1878).

Salomão Bensabat Saragga (1845-1900) — Owner and editor of the magazine Os Dois Mundos: Illustração para Portugal e Brazil (1877).

António Manuel da Cunha e Sá (1854-1909) — Director of Mail Services at Lisbon’s Central Station; author of the historical novels Da Parte D’El-Rei (From the King) (1873) and Da Parte da Rainha (From the Queen) (1874).

Agostinho Barbosa de Sottomayor (1845-1923) — Judge.

Pedro de Alcântara Vidoeira (1834-1917) — Writer, journalist and cultural critic; author, among others, of A Fidalga do Juncal (The Noblewoman of Juncal) (1904) and Nova Lírica Popular (New Popular Lyric) (1913).

Note — It was not possible to find any kind of biographical information regarding the following translators: Pompeu Garrido, Francisco Gomes Moniz, Diogo do Carmo Reis, Napoleão Toscano and J.B. Pinto da Silva.

Attachment 2 - Jules Verne, edition in Portugal (1874-2021)

Research made in April and May 2022 in the following collections: Biblioteca Nacional de Portugal (National Library of Portugal), Catálogo Colectivo de Bibliotecas dos Açores (Public Libraries of Azores Collective Catalog), Rede de Bibliotecas Municipais de Lisboa (Lisbon Public Libraries Network), Rede de Bibliotecas Municipais de Oeiras (Oeiras Public Libraries Networks), Biblioteca João Paulo II da Universidade Católica de Portugal (Library John Paul II of Catholic University of Portugal) and the blog JvernePt.

1 - The chronology of Verne’s works follows the original publication date of Hetzel’s edition in a single volume. The author’s remaining texts that have not been included in this edition are presented according to their first publication date;

2 - The bibliographic information presented here was possible by cross-referencing information in the above mentioned libraries;

3- The bibliographic data keep the Portuguese language’s spelling used when the works were published in Portugal;

4 - The citation order is as follows: publication date, publication place, publisher, edition’s number and translator’s name.

1863 Cinco semanas em balão (Cinq Semaines en ballon)

- 1875, Lisboa, Empreza Horas Românticas, 1ª edição, tradução de Francisco Augusto Correia Barata

- 1881, Lisboa, Empreza Horas Românticas, 2ª edição, tradução de Francisco Augusto Correia Barata

- 1886, Lisboa, David Corazzi, 3ª edição, tradução de Francisco Augusto Correia Barata

- 1909, Lisboa, A Editora, 5ª edição, tradução de Francisco Augusto Correia Barata

- 195?, Lisboa, Bertrand, 7ª edição, tradução de Francisco Augusto Correia Barata

- 1957, Lisboa, Bertrand, 10ª edição, tradução de Francisco Augusto Correia Barata

- 1957, Lisboa, Bertrand, 11ª edição, tradução de Francisco Augusto Correia Barata

- 1963, Lisboa, Bertrand, 1ª edição, tradução de Alfredo Silva

- 1967, Lisboa, Bertrand, S/I, tradução de Francisco Augusto Correia Barata

- 1970, Lisboa, Editorial IBIS, 1ª edição, tradução de Alfredo Silv

- 1972, Lisboa, Bertrand, 2ª edição, tradução de Alfredo Silva

- 1980, Lisboa, Amigos do Livro, 1ª edição, tradução e revisão de S. Pinto

- 1982, Mem Martins, Europa-América, 1ª edição, tradução de Amarina Alberty

- 1990, Lisboa, Livros do Brasil, 1ª edição, tradução de J. Lima da Costa

- 1991, Mem Martins, Europa-América, 2ª edição, tradução de Amarina Alberty

- 1995, Lisboa, Círculo de Leitores, 1ª edição, tradução de Gabriela Corte Real

- 1999, Alfragide, Ediclube, 1ª edição, S/N

- 2002, Lisboa, Correio da Manhã, 1ª edição, tradução de Francisco Augusto Correia Barata

- 2003 Barcelona, Editorial RBA, 1ª edição, tradução de Francisco Augusto Correia Barata

- 2005, Porto, Público - Comunicação Social SA, 1ª edição, tradução de Francisco Augusto Correia Barata

- 2012, Lisboa, 11x17, 1ª edição, tradução de Francisco Augusto Correia Barata (revisão de Carla Barbosa)

- 2018, Lisboa,11x17, 1ª edição reimp., tradução de Francisco Augusto Correia Barata (revisão de Carla Barbosa)

1864 Viagem ao centro da Terra (Voyage au centre de la Terre)

- 1875, Lisboa, Empreza Horas Românticas, 1ª edição, tradução de Mariano Cyrillo de Carvalho

- 1886, Lisboa, David Corazzi, 3ª edição, tradução de Mariano Cyrillo de Carvalho

- 1956, Lisboa, Bertrand, 1ª edição, tradução de Mariano Cyrillo de Carvalho

- 1968, Lisboa, Bertrand, 2ª edição, tradução de Mariano Cyrillo de Carvalho

- 197?, Mem Martins, Europa-América, 1ª edição, S/N

- 1973, Amadora, Bertrand, 3ª edição, tradução de Mariano Cyrillo de Carvalho

- 1978, Lisboa, SEL.1978, 1ª edição, tradução de Ricardo Alberty

- 1979, Porto, Edinter, 1ª edição, S/N

- 198?, Lisboa, Amigos do Livro, 1ª edição, Tradução e revisão de F. Romão

- 1980, Lisboa, Círculo de Leitores, 1ª edição, S/N

- 1980, Porto, Porto Editora, 1ª edição, S/N

- 1981, Amadora, Bertrand, 4ª edição, tradução de Mariano Cyrillo de Carvalho

- 1986, Lisboa, Pública, 1ª edição, tradução de Maria Auta de Barros

- 1987, Porto, Porto Editora,1ª edição reimp., S/N

- 1987, Porto, Edinter, 1ª edição reimp., S/N

- 1988, Porto, Civilização, 1ª edição, tradução de M. Alice Moura Bessa

- 1988, Lisboa, Livros do Brasil, 1ª edição, tradução de J. Lima da Costa

- 1989, Mem Martins, Europa-América, 2ª edição, tradução de Lídia Jorge

- 1995, Lisboa, Círculo de Leitores, 1ª edição, tradução de J. Lima da Costa e Isabel St. Aubyn

- 1999, Mem Martins, Europa-América, 3ª edição, tradução de Lídia Jorge

- 1999, Alfragide, Ediclube, 1ª edição, S/N

- 2003, Lisboa, Correio da Manhã, 1ª edição, tradução de Mariano Cyrillo de Carvalho

- 2003, Barcelona, Editorial RBA, 1ª edição, tradução de Mariano Cyrillo de Carvalho

- 2004, Porto, Público - Comunicação Social SA, 1ª edição, tradução de Mariano Cyrillo de Carvalho

- 2008, Mem-Martins, Europa-América 3ª Lídia Jorge

- 2008, Matosinhos, Quid Novi, 1ª edição, tradução de Mariano Cyrillo de Carvalho (revisão de Dora Santos)

- 2010, Lisboa, 11x17, 1ª edição, tradução de J. Lima da Costa

- 2013, Lisboa, 11x17, 2ª edição, tradução de J. Lima da Costa (revisão de Duarte Camacho)

- 2014, Lisboa, 11x17, 2ª edição reimp., tradução de J. Lima da Costa

- 2014, Sintra, Girassol, 1ª edição, tradução de Joana Rosa

- 2015, Lisboa, 11x17, 2ª edição reimp., tradução de J. Lima da Costa

- 2016, Lisboa, Relógio d’ Água, 1ª edição, tradução de Maria Matta Antunes

- 2017, Lisboa, 11x17, 2ª edição reimp., tradução de J. Lima da Costa

- 2019, Lisboa, 11x17, 2ª edição reimp., tradução de J. Lima da Costa

- 2021, Porto, Porto Editora, 1ª edição, tradução de J. Lima da Costa

- 2021, Forte da Casa, Clássica Editora, 1ª edição, S/N

1865 Da Terra à lua (De la Terre à la Lune)

- 1874, Lisboa, Empreza Horas Românticas, 1ª edição, tradução de Henrique de Macedo

- 187?, Lisboa, Empreza Horas Românticas, 2ª edição, tradução de Henrique de Macedo

- 1878, Lisboa, Empreza Horas Românticas, 3ª edição, tradução de Henrique de Macedo

- 1886, Lisboa, David Corazzi, 4ª edição, tradução de Henrique de Macedo

- 1886, Lisboa, David Corazzi, 5ª, tradução de Henrique de Macedo

- 1905, Lisboa, A Editora, 5ª edição, tradução de Henrique de Macedo

- 193?, Lisboa, Aillaud e Bertrand, 7ª edição, tradução de Henrique de Macedo

- 195?, Lisboa, Bertrand, 8ª edição, tradução de Henrique de Macedo

- 1960, Mem Martins, Europa-América, 1ª edição, tradução de Cascais Franco

- 1965, Lisboa, Editorial Aster, 1ª edição, tradução de Mendes da Costa

- 1968, Amadora, Bertrand, S/I, tradução de Henrique de Macedo

- 1975, Amadora, Bertrand, S/I, tradução de Henrique de Macedo

- 1975, Porto, Figueirinhas, 1ª edição, S/N

- 1980, Porto, Porto Editora, 1ª edição, S/N

- 1985, Lisboa, Amigos do Livro 1ª edição, tradução de S. Pinto

- 1985, Mem Martins, Europa-América, 2ª edição, tradução de Cascais Franco

- 1987, Porto, Porto Editora, 2ª edição, S/N

- 1993, Lisboa, Livros do Brasil, 1ª edição, tradução de J. Lima da Costa

- 1995, Lisboa, Círculo de Leitores, 1ª edição, tradução de Isabel St. Aubyn

- 1999, Alfragide, Ediclube, 1ª edição, S/N

- 2003, Barcelona, Editorial RBA, 1ª edição, tradução de Henrique de Macedo

- 2003, Lisboa, Correio da Manhã, 1ª edição, tradução de Henrique de Macedo

- 2005, Porto, Público - Comunicação Social SA, 1ª edição, tradução de Henrique de Macedo

- 2011, Lisboa, 11x17, 1ª edição, tradução de Isabel St. Aubyn (revisão de Cristina Vaz)

- 2014, Lisboa, 11x17, 1ª edição reimp., tradução de Isabel St. Aubyn (revisão de Cristina Vaz)

- 2018, Lisboa, 11x17, 1ª edição reimp., tradução de Isabel St. Aubyn (revisão de Cristina Vaz)

- 2020, Forte da Casa, Clássica Editora, 1ª edição, tradução de Cascais Franco

1866 Aventuras do capitão Hatteras (Voyages et Aventures du capitaine Hatteras)

- 1874, Lisboa, Empreza Horas Românticas, 1ª edição, tradução de Henrique de Macedo

- 1879, Lisboa, Empreza Horas Românticas, 2ª edição, tradução de Henrique de Macedo

- 1886, Lisboa, David Corazzi, 3ª edição, tradução de Henrique de Macedo

- 1910, Lisboa, A Editora, 5ª edição, tradução de Henrique de Macedo///////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////

- 1910, Lisboa, A Editora, 5ª edição, tradução de Henrique de Macedo

- 1912, Lisboa, A Editora, S/I, tradução de Henrique de Macedo

- 192?, Lisboa, Aillaud e Bertrand, 6ª edição, tradução de Henrique de Macedo

- 1935, Lisboa, Aillaud e Bertrand, 7ª edição, tradução de Henrique de Macedo

- 1958, Lisboa, Bertrand, 10ª edição, tradução de Henrique de Macedo

- 1960, Mem Martins, Europa-América, 1ª edição, tradução de Pilar Delvaulx

- 1970, Lisboa, Bertrand, 1ª edição, tradução de Henrique de Macedo

- 1977, Amadora, Bertrand, S/I, tradução de Henrique de Macedo

- 1983, Mem Martins, Europa-América, 2ª edição, tradução de Pilar Delvaulx

- 2003, Barcelona, Editorial RBA, 1ª edição, tradução de Henrique de Macedo

- 2005, Porto, Público - Comunicação Social SA, 1ª edição, tradução de Henrique de Macedo

1868 Os filhos do capitão Grant (Les Enfants du capitaine Grant)

- 1875, Lisboa, Empreza Horas Românticas, 1ª edição, tradução de A. M. da Cunha e Sá

- 187?, Lisboa, Empreza Horas Românticas, S/I, tradução de A. M. da Cunha e Sá

- 1886, Lisboa, David Corazzi, 3ª edição, tradução de A. M. da Cunha e Sá

- 1915, Lisboa, Aillaud e Bertrand, 4ª edição, A. M. da Cunha e Sá

- 1920, Lisboa, Bertrand, 5ª edição, tradução de A. M. da Cunha e Sá

- 1958, Lisboa, Bertrand, 7ª edição, tradução de A. M. da Cunha e Sá

- 195?, Lisboa, Bertrand, 8ª, tradução de A. M. da Cunha e Sá

- 195?, Lisboa, Bertrand, 9ª edição, tradução de A. M. da Cunha e Sá

- 196?, Lisboa, Bertrand, S/I, tradução de A. M. da Cunha e Sá

- 1970, Amadora, Ibis, S/I, S/I

- 1971, Venda Nova, Ibis, S/I, S/I

- 1977, Lisboa, Scire, 1ª edição, tradução de F. Sobral

- 1979, Mem Martins, Europa-América, 1ª edição, tradução de Eduardo Saló

- 1986, Lisboa Pública 1ª S/I

- 1987, Mem Martins, Europa-América, 1ª edição, tradução de Ana Rabaça

- 1989, Lisboa, Livros do Brasil, 1ª edição, tradução de J. Lima da Costa

- 1995, Lisboa, Círculo de Leitores, 1ª edição, tradução de J. Lima da Costa

- 2003, Barcelona, Editorial RBA, 1ª edição, tradução de A. M. da Cunha e Sá

- 2005, Porto, Público - Comunicação Social SA, 1ª edição, tradução de A. M. da Cunha e Sá

1870 À volta da lua (Autour de la Lune)

- 1874, Lisboa, Empreza Horas Românticas, 1ª edição, tradução de Henrique de Macedo

- 1879, Lisboa, Empreza Horas Românticas, 2ª edição, tradução de Henrique de Macedo

- 1886, Lisboa, David Corazzi, 4ª edição, tradução de Henrique de Macedo

- 1886, Lisboa, David Corazzi, 5ª edição, tradução de Henrique de Macedo

- 1904, Lisboa, A Editora, 5ª edição, tradução de Henrique de Macedo

- 193?, Lisboa, Bertrand, 9ª edição, tradução de Henrique de Macedo

- 1956, Lisboa, Bertrand, 11ª edição tradução de Henrique de Macedo

- 1960, Lisboa, Aster, 1ª edição, tradução de Mendes Costa

- 1965, Lisboa, Aster, 2ª edição, tradução de Mendes Costa

- 1968, Lisboa, Bertrand, S/I, tradução de Henrique de Macedo

- 1985, Mem Martins, Europa-América, S/I, tradução de Cascais Franco

- 1985, Lisboa, Amigos do Livro, 1ª edição, tradução de F. Romão

- 1999, Alfragide, Ediclube, 1ª edição, S/N

- 2003, Barcelona, Editorial RBA, 1ª edição, tradução de Henrique de Macedo

- 2009, Mem Martins, Europa-América, S/I, tradução de Cascais Franco

- 2011, Lisboa, 11x17, 1ª edição, tradução de Isabel St. Aubyn (revisão de Carla Barbosa)

- 2020, Forte da Casa, Clássica Editora, 1ª edição, tradução de Cascais Franco

1870 Os primeiros exploradores (Découverte de la terre: Histoire générale des grands voyages et des grands voyageurs - Les Premiers explorateurs)

- 1879, Lisboa, Empreza Horas Românticas, 1ª edição, tradução de Manuel Pinheiro Chagas

- 1889, Lisboa, Companhia Nacional Editora, 2ª edição, tradução de Manuel Pinheiro Chagas

- 193?, Lisboa, Aillaud e Bertrand, 3ª edição, tradução de Manuel Pinheiro Chagas

- 195?, Lisboa, Bertrand, 5ª edição, tradução de Manuel Pinheiro Chagas

- 1973, Amadora, Bertrand, S/I, tradução deManuel Pinheiro Chagas

- 2003, Barcelona, Editorial RBA, 1ª edição, tradução de Manuel Pinheiro Chagas

1871 Vinte mil léguas submarinas (Vingt Mille Lieues sous ler mers)

- 1876, Lisboa, Empreza Horas Românticas, 1ª edição, tradução de Gaspar Borges de Avellar e Francisco Gomes Moniz

- 1887, Lisboa, David Corazzi, 2ª edição, tradução de tradução de Gaspar Borges de Avellar e Francisco Gomes Moniz

- 1909, Lisboa, A Editora, S/I, tradução de tradução de Gaspar Borges de Avellar e Francisco Gomes Moniz

- 1935, Lisboa, S/I, 4ª edição, tradução de Gaspar Borges de Avellar e Francisco Gomes Moniz

- 195?, Lisboa, Bertrand, 6ª edição, tradução de Gaspar Borges de Avellar e Francisco Gomes Moniz

- 195?, Lisboa, Bertrand, 8ª edição, tradução de Gaspar Borges de Avellar e Francisco Gomes Moniz

- 1971, Porto, Liv. Figueirinhas, 1ª edição, S/N

- 1973, Lisboa, Círculo de Leitores, 1ª edição, tradução de Gaspar Borges de Avellar e Francisco Gomes Moniz (revisão de Clara Joana)

- 1973, Lisboa, Bertrand, 3ª edição, tradução de Gaspar Borges de Avellar e Francisco Gomes Moniz

- 1979, Porto, Edinter, 1ª edição, S/N

- 1980, Lisboa, Amigos do Livro, 1ª edição, tradução de F. Romão

- 1980, Mem Martins, Europa-América, 2ª edição, tradução de M. de Campos

- 1981, Lisboa, Bertrand, 4ª edição, tradução de Gaspar Borges de Avellar e Francisco Gomes Moniz

- 1986, Lisboa, Pública, 1ª edição, tradução de Maria Auta de Barros

- 1987, Porto, Edinter, 2ª edição, S/N

- 1989, Lisboa, Livros do Brasil, 1ª edição, tradução de J. Lima da Costa

- 1989, Mem Martins, Europa-América, 3ª edição, tradução de M. de Campos

- 1996, Lisboa, Círculo de Leitores, 2ª edição, tradução de Gaspar Borges de Avellar e Francisco Gomes Moniz

- 1999, Porto, Civilização, 1ª edição, tradução de Mafalda Morais Marques

- 1999, Mem Martins, Europa-América, 4ª edição, tradução de M. de Campos

- 1999, Alfragide, Ediclube, 1ª edição, S/N

- 2000, Lisboa, Verbo, 1ª edição, tradução de Isabel Simões dos Santos

- 2003, Lisboa, Correio da Manhã, 1ª edição, tradução de Gaspar Borges de Avellar e Francisco Gomes Moniz

- 2003, Barcelona, Editorial RBA, 1ª edição, tradução de Gaspar Borges de Avellar e Francisco Gomes Moniz

- 2005, Porto, Público - Comunicação Social SA, 1ª edição, tradução de Elsa Patrício de Barros

- 2007, Mem Martins, Europa-América, 5ª edição, tradução de M. de Campos

- 2011, Lisboa, 11x17, 1ª edição, tradução de Gaspar Borges de Avellar e Francisco Gomes Moniz (revisão de Eda Lyra)

- 2012, Sintra, Girassol, 1ª edição, tradução de Maria João Rodrigues (revisão de Luís Candeias)

- 2014, Sintra, Girassol, 1ª edição, tradução de Joana Rosa

- 2014 Lisboa, 11x17, 1ª edição reimp., tradução de Gaspar Borges de Avellar e Francisco Gomes Moniz (revisão de Eda Lyra)

- 2017, Lisboa, Relógio d' Água, 1ª edição, tradução de Carlos Correia Monteiro de Oliveira

- 2021, Forte da Casa, Clássica Editora, 1ª edição, S/N

1871 Uma cidade flutuante (Une ville flottante)

- 1877, Lisboa, Empreza Horas Românticas,1ª edição, tradução de Pedro Guilherme dos Santos Diniz

- 1887, Lisboa, David Corazzi, 2ª edição, tradução de Pedro Guilherme dos Santos Diniz

- 195?, Lisboa, Bertand, 5ª edição, tradução de Pedro Guilherme dos Santos Diniz

- 195?, Lisboa, Bertand, 7ª edição, tradução de Pedro Guilherme dos Santos Diniz

- 1970, Mem Martins, Europa-América, S/I, tradução de Maria Gabriela de Bragança

- 1972, Amadora, Bertrand, S/I, tradução de Pedro Guilherme dos Santos Diniz

- 1978, Amadora, Bertrand, S/I, tradução de Pedro Guilherme dos Santos Diniz

- 1983, Mem Martins, Europa-América, S/I, Maria Gabriela de Bragança

- 1995, Lisboa, Círculo de Leitores, 1ª edição, tradução de Gabriela Corte Real

- 1999, Alfragide, Ediclube, 1ª edição, tradução de Pedro Guilherme dos Santos Diniz

- 2003, Barcelona, Editorial RBA, 1ª edição, tradução de Pedro Guilherme dos Santos Diniz

- 2005, Porto, Público - Comunicação Social SA, 1ª edição, tradução de Pedro Guilherme dos Santos Diniz

1871 Os violadores do bloqueio (Les Forceurs de blocus)

- 1877, Lisboa, Empreza Horas Românticas,1ª edição, tradução de Pedro Guilherme dos Santos Diniz

- 1972, Amadora, Bertrand, 1ª edição, tradução de Pedro Guilherme dos Santos Diniz

- 1987, Lisboa, Futura, 1ª edição, tradução de Jorge Magalhães

- 2003, Barcelona, Editorial RBA, 1ª edição, tradução de Pedro Guilherme dos Santos Diniz

1872 Aventuras de três russos e três ingleses (Aventures de trois Russes et de trois Anglais dans l'Afrique australe)

- 1875,Lisboa, Empreza Horas Românticas, 1ª edição, tradução de Marianno Cyrillo de Carvalho

- 1886, Lisboa, David Corazzi, 3ª edição, tradução de Marianno Cyrillo de Carvalho

- 1910, Lisboa, A Editora, 4ª edição, tradução de Marianno Cyrillo de Carvalho

- 1969, Lisboa, Bertrand, S/I, tradução de Marianno Cyrillo de Carvalho

- 1978 Amadora, Bertrand, S/I, tradução de Mariano Cirilo de Carvalho

- 2003, Barcelona, Editorial RBA, 1ª edição, tradução de Mariano Cirilo de Carvalho

- 2005, Porto, Público - Comunicação Social SA, 1ª Edição, tradução de Mariano Cirilo de Carvalho

1873 O país das peles (Le Pays des fourrures)

- 1877, Lisboa, Empreza Horas Românticas, 1ª edição, tradução de Maryanno Cyrillo de Carvalho

- 1887, Lisboa, David Corazzi, 2ª edição, tradução de Maryanno Cyrillo de Carvalho

- 1908, Lisboa, A Editora, S/I, tradução de Maryanno Cyrillo de Carvalho

- 1912, Lisboa A Editora, 3ª edição, tradução de Maryanno Cyrillo de Carvalho

- 192?, Lisboa, Aillaud e Bertrand, S/I, tradução de Maryanno Cyrillo de Carvalho

- 195?, Lisboa, Bertrand, 6ª edição, tradução de Maryanno Cyrillo de Carvalho

- 1970, Amadora, Bertrand, S/I, tradução de Mariano Cyrillo de Carvalho

- 2003, Barcelona, Editorial RBA, 1ª edição, tradução de Mariano Cirilo de Carvalho

- 2005, Porto, Público - Sociedade de Comunicação SA, 1ª edição, tradução de Mariano Cyrillo de Carvalho

1873 A volta ao mundo em oitenta dias (Le Tour du monde en quatre-vingts jours)

- 1874, Lisboa, Empreza Horas Românticas, 1ª edição, tradução de A.M. da Cunha e Sá

- 1886, Lisboa, David Corazzi, 3ª edição, tradução de A.M. da Cunha e Sá

- 1905, Lisboa, A Editora, 4ª edição, tradução de A.M. da Cunha e Sá

- 1934, Lisboa, Bertrand, 7ª edição, tradução de A.M. da Cunha e Sá

- 195?, Lisboa, Bertrand, 12ª edição, tradução de A.M. da Cunha e Sá

- 1956, Lisboa, Bertrand, S/I, tradução de A.M. da Cunha e Sá

- 1966, Lisboa, Aster, 1ª edição, tradução de Mendes Costa

- 1967, Lisboa, Bertrand, S/I, tradução de A.M. da Cunha e Sá

- 1967, Lisboa, Bertrand, 2ª edição, tradução de Paulo de Mascarenhas

- 1973, Lisboa, Bertrand, S/I, tradução de A.M. da Cunha e Sá

- 1974, Lisboa, Editores Associados, 1ª edição, tradução de A.M. da Cunha e Sá

- 1975, Lisboa, Bertrand, S/I, tradução de A.M. da Cunha e Sá

- 1977, Lisboa, Pública, 1ª edição, tradução de Maria Auta de Barros

- 1979, Lisboa, Verbo, 1ª edição, tradução de João Forte

- 1981, Lisboa, Bertrand, S/I, tradução de A.M. da Cunha e Sá

- 1981, Mem Martins, Europa-América, 1ª edição, tradução de Ana Cristina Pinto

- 1982, Mem Martins, Europa-América, 1ª edição reimp., tradução de Ana Cristina Pinto

- 1984, Lisboa, Bertrand, S/I, tradução de A.M. da Cunha e Sá

- 1984, Lisboa, Publicit, S/I, S/N

- 1985, Lisboa, Pública, 2ª edição, tradução de Maria Auta de Barros

- 1985, Lisboa, Amigos do Livro, 1ª edição, tradução de S. Pinto

- 1986, Lisboa, Círculo de Leitores, 1ª edição, tradução de A.M. da Cunha e Sá

- 1987, Porto, Edinter, 1ª edição, S/N

- 1988, Lisboa, Bertrand, S/I, tradução de Paulo de Mascarenhas

- 1988, Porto, Civilização, 1ª edição, tradução de Maria Alice Moura Bessa

- 1989, Lisboa, Bertrand, S/I, tradução de A.M. da Cunha e Sá

- 1989, Mem Martins, Europa-América, 2ª edição, tradução de Ana Cristina Pinto

- 1989, Lisboa, Dom Quixote, 1ª edição, tradução de A.M. da Cunha e Sá (revisão de Ayala Monteiro)

- 1993, Lisboa, Verbo, 1ª edição, tradução de Maria das Mercês de Mendonça Soares

- 1994, Lisboa, Livros do Brasil, 1ª edição, tradução de J. Lima da Costa

- 1995, Lisboa, Dom Quixote, 2ª edição, tradução de A.M. da Cunha e Sá (revisão de Ayala Monteiro)

- 1996, Lisboa, Verbo, 1ª edição, tradução de Maria das Mercês de Mendonça Soares

- 1998, Lisboa, Ulisseia, 1ª edição, S/N

- 1999, Alfragide, Ediclube, 1ª edição, S/N

- 2000, Mem Martins, Europa-América, 3ª edição, tradução de Ana Cristina Pinto

- 2002, Lisboa, Correio da Manhã, 1ª edição, tradução de A.M. da Cunha e Sá

- 2003, Barcelona, Editorial RBA, 1ª edição, tradução de A.M. da Cunha e Sá

- 2004, Porto, Público - Sociedade de Comunicação SA, 1ª edição, tradução de Lúcia do Carmo Cabrita

- 2008, Matosinhos, Quid Novi, 1ª edição, tradução de A.M. da Cunha e Sá

- 2011, Lisboa, 11x17, 1ª edição, tradução de A.M. da Cunha e Sá (revisão de Eda Lyra)

- 2011, Barcelona, Sic Idea y Creación, 1ª edição, tradução de Roberto Marques

- 2012, Lisboa, Zero a Oito, 1ª edição, tradução de Carla Pacheco

- 2013, Lisboa, 11x17, 1ª edição reimp., tradução de A.M. da Cunha e Sá (revisão de Eda Lyra)

- 2014, Lisboa, 11x17, 1ª edição reimp., tradução de A.M. da Cunha e Sá (revisão de Eda Lyra)

- 2015, Lisboa, 11x17, 1ª edição reimp., tradução de A.M. da Cunha e Sá (revisão de Eda Lyra)

- 2016, Lisboa, Guerra e Paz, 1ª edição, tradução de Helder Guégués

- 2017, Amadora, Fábula, 1ª edição, tradução de Tiago Marques

- 2017, Lisboa, Pomar, 1ª edição, tradução de Jorge Colaço

- 2017, Lisboa, Relógio d’Água, 1ª edição, tradução de Pedro Ventura

- 2019, Amadora, Fábula, 2ª edição, tradução de Tiago Marques

- 2019, Barcarena, Presença, 1ª edição, tradução de Carlos Grifa Babo

- 2019, Porto, Porto Editora, 1ª edição, tradução de A.M. da Cunha e Sá

- 2019, Lisboa, Círculo de Leitores, 1ª edição, tradução de Marta Pinho

- 2020, Tentúgal, Europrice, 1ª edição, tradução de Cláudia Gonçalves

- 2021, Amadora, Fábula, 3ª edição, tradução de Tiago Marques

1874 O Doutor Ox (Le Docteur Ox)

- 1878, Lisboa, Empreza Horas Românticas, 1ª edição, tradução de A.M. da Cunha e Sá

- 1888, Lisboa, David Corazzi, 2ª edição, tradução de A.M. da Cunha e Sá

- 195?, Lisboa, Bertrand, 4ª edição, tradução de A.M. da Cunha e Sá

- 1960, Lisboa, Bertrand, 6ª edição, tradução de A.M. da Cunha e Sá

- 1967, Lisboa, Bertrand, S/I, tradução de A.M. da Cunha e Sá

- 1975, Amadora, Bertrand, S/I, tradução de A.M. da Cunha e Sá

- 2003, Barcelona, Editorial RBA, 1ª edição, tradução de A.M. da Cunha e Sá

1874 Um drama nos ares (Un drame dans les airs) – publicado em O Doutor Ox

- 1878, Lisboa, Empreza Horas Românticas, 1ª edição, tradução de A.M. da Cunha e Sá

- 1971, Lisboa, Arcádia, tradução de Lima da Costa (In Os melhores contos)

- 2003, Barcelona, Editorial RBA, 1ª edição, tradução de A.M. da Cunha e Sá

1874 Mestre Zaccharius (Maître Zacharius ou l'Horloger qui avait perdu son âme) – publicado em O Doutor Ox

- 1878, Lisboa, Empreza Horas Românticas, 1ª edição, tradução de A.M. da Cunha e Sá

- 1978, Lisboa, Edições António Ramos, 1ª edição, tradução de Ana Maria Rabaça (in Histórias Inesperadas)

- 2003, Barcelona, Editorial RBA, 1ª edição, tradução de A.M da Cunha e Sá

1874 Uma invernada nos gelos (Un hivernage dans les glaces) – publicado em O Doutor Ox

- 1878, Lisboa, Empreza Horas Românticas, 1ª edição, tradução de A.M. da Cunha e Sá

- 2003, Barcelona, Editorial RBA, 1ª edição, tradução de A.M. da Cunha e Sá

1875 A ilha misteriosa (L'Île mystérieuse)

- 1876, Lisboa, Empreza Horas Românticas, 1ª edição, tradução de Henrique de Macedo

- 1887, Lisboa, David Corazzi, 2ª edição, tradução de Henrique de Macedo

- 1909, Lisboa, A Editora, S/I, tradução de Henrique de Macedo

- 1912, Lisboa, A Editora, 3ª edição, tradução de Henrique de Macedo

- 1960, Mem Martins, Europa-América, 1ª edição, tradução de Torquato Fernandes

- 1972, Venda Nova, Íbis, 1ª edição, tradução de Jaime Más

- 1974, Amadora, Bertrand, S/I, tradução de Henrique de Macedo

- 1975, Lisboa, Círculo de Leitores, 1ª edição, tradução de José Valente Pires

- 1976, Lisboa, Editorial Scire, 1ª edição, tradução de João A. Campos

- 1979, Porto, Edinter 1ª edição, S/N

- 198?, Lisboa, Amigos do Livro, 1ª edição, tradução de F. Romão

- 1982, Mem Martins, Europa-América, 2ª edição, tradução de Torquato Fernandes

- 1982, Amadora, Bertrand, S/I, tradução de Henrique de Macedo

- 1983, Lisboa, Pública, 1ª edição, S/N

- 1987, Porto, Edinter, 2ª edição, S/N

- 1991, Lisboa, Livros do Brasil, 1ª edição, tradução de J. Lima da Costa

- 1996, Lisboa, Círculo de Leitores, 1ª edição, tradução de J. Lima da Costa

- 1996, Lisboa, Verbo, 1ª edição, tradução de Isabel Simões dos Santos

- 2000 Lisboa, Verbo, 2ª edição, tradução de Isabel Simões dos Santos

- 2000, Mem Martins, Europa-América, 2ª edição, tradução de Torquato Fernandes

- 2003, Lisboa, Correio da Manhã, 1ª edição, tradução de Henrique de Macedo

- 2003, Barcelona, Editorial RBA, 1ª edição, tradução de Henrique de Macedo

- 2005, Porto, Público - Sociedade de Comunicação SA, 1ª edição, tradução de Henrique de Macedo

- 2017, Tentúgal, Europrice, 1ª edição, tradução de T. Florindo

1875 A galera Chancellor (Le Chancellor)

- 1878, Lisboa, Empreza Horas Românticas, 1ª edição, tradução de Mariano Cyrillo de Carvalho

- 1888, Lisboa, David Corazzi, 3ª edição, tradução de Marianno Cyrillo de Carvalho

- 192?, Lisboa, Aillaud e Bertrand, S/I, tradução de Marianno Cyrillo de Carvalho

- 195?, Lisboa, Bertrand, 2ª edição, tradução de Mariano Cirilo de Carvalho

- 1970, Amadora, Bertrand, S/I, tradução de Mariano Cirilo de Carvalho

- 1978, Amadora, Bertrand, S/I, tradução de Mariano Cirilo de Carvalho

- 1999, Alfragide, Ediclube, 1ª edição, S/N

- 2002, Amadora, Bertrand, S/I, tradução de Mariano Cirilo de Carvalho

- 2003, Barcelona, Editorial RBA, 1ª edição, tradução de Mariano Cirilo de Carvalho

- 2019, Lisboa, Sistema Solar, 1ª edição, tradução de Aníbal Fernandes