Among the several important interviews that Jules Verne gave to journalists, there remained one yet to be tracked down―and which was, in fact, the first since Adrien Marx's and Charles Raymond's published texts (1873 and 1875 respectively) which were reports rather than real interviews [1]. Its existence was known through a letter written by Jules Verne to the interviewer Henri Pène du Bois. This letter thanks the journalist for sending him a copy of the journal in which the interview was published. This letter written by Verne is a confirmation of the authenticity of the interview [2]:

|

|

Letter written by Jules Verne to Henri Pène du Bois and the two sides of the envelope used to mail it from Amiens to New York (Musée Jules Verne, Nantes)

Amiens, 17 Juillet 87. [3]

Cher Monsieur,

En même temps que votre lettre, je viens de recevoir le numéro du Journal que vous avez bien voulu me faire adresser. Je vous en remercie. Je n’ai pu que lire superficiellement votre article, et je vais me le faire traduire ; mais j’ai compris cependant que vous aviez très fidèlement reproduit les diverses phases de notre causerie toute intime. C’est un grand bonheur pour moi que les Américains aient pu juger des sentiments de profonde sympathie que j’éprouve pour leur pays et pour eux. Je vous l’ai dit, mon plus grand désir serait d’y retourner.

Je serai très heureux si je puis me rencontrer un jour avec M. G. Bennett [4], et, si vous êtes en rapport avec M. Cyrus Field [5], veuillez lui rappeler, je vous prie, que j’ai eu l’avantage de voyager avec lui à bord du Great Eastern dans son voyage de Liverpool à New-York en 1867.

Et maintenant, cher monsieur, je vous serre cordialement la main, et vous prie de me croire

Tout votre

Jules Verne

Amiens, July 17, 87.

Dear Sir,

In the same mail with your letter, I have just received the issue of the Newspaper you kindly sent me. I thank you for it. I have only been able to read your article superficially, and I will have it translated although I have understood that you have reproduced very faithfully the various phases of our very personal talk. It is a great satisfaction for me to know that the American people have been able to appreciate my deep feelings of sympathy for their country and for them. As I have told you, my greatest desire would be to go back.

I shall be very glad if I may one day meet with Mr. G. Bennett, and if you are in touch with Mr. Cyrus Field, please remind him that I had the advantage of traveling with him on the Great Eastern on her crossing from Liverpool to New York in 1867.

And now, dear sir, I cordially shake your hand, and assure you of by best wishes

All yours

Jules Verne

The Great Eastern off the coast of Southampton. Stereoscopic view by G. W. Wilson, around 1867 (coll. Dehs).

Although this letter gives us the identity of the author and the approximate date of publication—July 1887—the name of the newspaper was unfortunately missing. The interview does not appear in the impressive Argus de la Presse (twenty-seven volumes), a collection of worldwide press clippings spanning more than fifty years which cover Hetzel's publications and authors. There were, however, a few clues—and they proved to be correct—to suggest that Pène's interview had been plagiarized by other American publications: in an anonymous article published by at least two newspapers [6] and in a book by Thomas William Herringshaw (1858-1927) [7]. The original, however, had yet to be found.

Henri (or Henry) Pène du Bois (1858-1906), of French descent, was an American journalist, bibliophile, art collector and specialist in bookbinding. Born in New Orleans, he was the nephew of the French writer and journalist Henry de Pène (1830-1888) who had used the pseudonym Nemo long before the birth of the captain with the same name [8]. Henri Pène du Bois was also the grandfather of the artist William (1916-1993) who illustrated in 1963 a noteworthy edition of Jules Verne's Dr. Ox's Experiment [9].

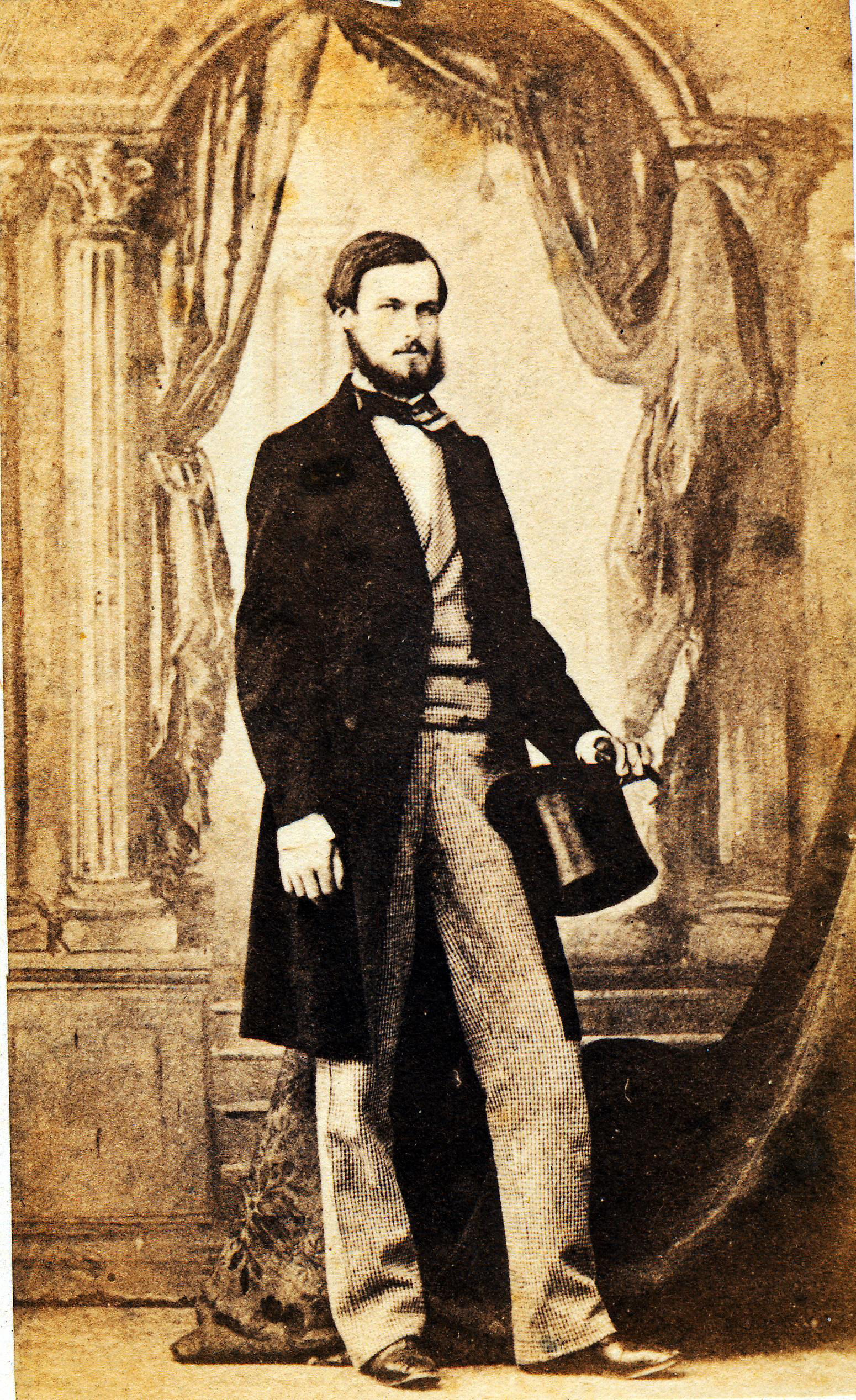

Henry de Pène (uncle of the journalist). Photograph by Franck (coll. Dehs).

Thanks to a tool recently made available by the Library of Congress [10], the search for the interview, ongoing for twenty years, was finally very easy to accomplish: it appeared on July 3, 1887 in The Indianapolis Journal (IN), p. 6, and is directly linked to the first American publication of the novel North Against South. An advertisement is printed on the same page of the newspaper [11]:

JULES VERNE’S GREAT STORY.

On the 10th of July the Journal will begin the publication of a new novel by Jules Verne, entitled “North and South, a Story of Love and War.” The romance is based upon the late civil war in the United States, a subject which, curiously enough, has not been used by any American novelist, save in an incidental way. A correspondent of the Journal gives an interesting account in another column of the circumstances which led the French writer to take up the topic. Whether the French writer will give his fancy the free play which has made some of his tales the marvelously entertaining creations they are, or whether he will adhere strictly to known facts in his treatment of the vast material at his command, is a matter for each reader to decide upon personally. In any case, it is certain that the story will be of absorbing interest, and of a character superior to a great majority of current fiction. The story will run for several months, and will appear in both the Sunday and weekly editions of the Journal.

In fact, this announcement is a kind of response to an article published in the same newspaper on February 21, 1887 (p. 2)—a copy of an article published by the Washington Post—quoting a very patriotic journalist who had declared himself rather disturbed by the theft of a the subject stolen from American authors by a “nimble little Frenchman”:

|

|

|

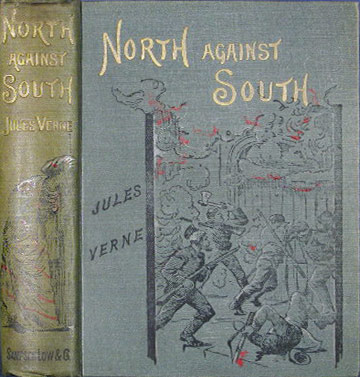

| Three bindings for the same novel Nord contre Sud (North Against South) | ||

| French, in-octavo Hetzel | American, Rand McNally | British, Sampson Low |

Page 6 of The Indianapolis Journal, July 3, 1887

The Coming American Romance.

The Washington Post says:

“It has been understood all along that the coming American novelist would portray the romantic side of our great civil war.

“From time to time critics, essayists and other piddlers in literature have called attention to this inviting theme. But it was agreed that there were difficulties in the way. It would not do to serve up our fratricidal struggle as a literary tit-bit until its rough edges had been worn off by time. It was generally admitted that our coming novelist would find his pie somewhere in this direction, but just here our litterateurs came to a full stop. They suggested, predicted, and did everything but tackle the subject in earnest.

“And now a nimble little Frenchman edges his way through the crowd and captures the prize. This bold raider is Jules Verne, and it goes without saying that he has helped himself to everything in sight. The title of his forthcoming story, ‘North and South; A Romance of the Civil War in America’ is a sufficient intimation that he is dealing with a big thing in a big way.

“It is a pity that Johnny Crapaud should have stolen a march on us, but we deserved it. For nearly a generation our coming novelists, for there were two of them, a Northerner and a Southerner, have been glowering at each other and bragging about the great unwritten war novel.

“It is useless to damn Jules Verne’s story in advance. He has shown his ability to interest the million, and the verdict of the literary upper-ten will not count. After all, what an author wants is to be read by the million. The patronage of the upper-ten would not support him. The Frenchman will give us a virile, vivid and graphic story. He may be a little behind on facts, but a man with his imagination can get along without facts. Perhaps our dilatory, namby-pamby novelists needed just such a lesson. At any rate, they have lost their pie, and when we taste it we shall be made to feel that it is an imported luxury.”

The Indianapolis Journal has secured the copyright of this romance for Indiana, and it will appear exclusively in the pages of the Sunday Journal so far as this territory is concerned. Of course, it will be a romance of rare power and interest—one of the greatest literary events of the time. Its publication will begin in April or May, the exact date not being yet agreed upon. It will run for nearly six month[s].

In January 1887, the play Around the World in 80 Days was on stage in Indianapolis [12], so Verne had already a presence there. The novel was first announced in The Indianapolis Journal on April 4, 1887 as The North and the South. The readers learned that the publication of the novel by “the eminent French Romancist”, was planned to be published in June. On July 8 the title was Texars's Revenge. A Story of Love and War!. The definitive title became Texar's Revenge. A Story of the American Civil War. The novel ran every Sunday from July 10 to October 16, 1887.

|

|

| The Indianapolis Journal | |

| April 7, 1887, p, 4 | July 8, 1887, p. 1 |

North Against South was translated twice into English [13]. The Indianapolis Journal published the same translation—translator unknown—as Rand, McNally & Company in Chicago or Sampson Low in London. The other translation, produced by Laura E. Kendall, was published by George Munro, who copyrighted Texar's Vengeance on July 29, 1887 [14]. Munro was probably confronted with the problem to find a new English title for the novel, both North Against South and Texar's Revenge being already used by The Indianapolis Journal.

The purpose of Henri Pène du Bois's interview was therefore to promote the launch of the serialization of North Against South and to anticipate possible partisan claims. Later interviews by Robert H. Sherard—he visited Jules Verne four times in Amiens— and Marie A. Belloc might appear more important for Vernian research than this one [15]. But this one precedes them and nothing similar had been published previously anywhere, in France or the United States. It is also obvious that Henri Pène du Bois did some research about Jules Verne before visiting him in Amiens. The author shows some memories of reading the articles published in 1875 by Adrien Marx, Charles Raymond and Jules Claretie [16]. Such facts make this interview interesting and worth publishing in its entirety.

M. JULES VERNE AT HOME

How the Famous French Novelist Began to Write Stories of Adventure.

Influence of Other Writers on His Work—How He Came to Write his Novel “North and South”—A Tale of the Civil War.

Written for the Sunday Journal.

The ancient capital of Picardy is, by the Northern railway to Boulogne and Calais, not further from Paris than is Philadelphia from New York. It is its misfortune. Amiens is charming; it has narrow streets through which eleven branches of the river Somme run, as the canals of Venice; quaintly-fashioned houses covered with tiles; wide boulevards that are well shaded; a citadel that was built by Henri IV and Vauban; a cathedral of the thirteenth century, that Violet-le-Duc [sic] [17] is authority for esteeming the ogival church “par excellence,” and than which there is not a nobler example of what Michelet aptly terms “sculptured prayer.” [18] The good suisse who unfolds the mysteries of that theological encyclopedia to the visitor is a dungeon of artistic lore, and he laments the fact that the rapid trains from Paris, in this age of progress, carry passengers to Calais without a break at Amiens.

This good suisse (a suisse is equivalent to a sexton) had the good fortune to meet in 1880, an enthusiastic writer, a Monsieur Rosquine—none other than the incomparable Ruskin [19], I afterward discovered—who gave him set phrases, phonetically written in French, for his use in addressing English-speaking persons. I copied one of them from his valuable, well-fingered note-book, that he guards as zealously as the ever-burning light in the altar. It reads thusly:

Ollendorf [sic] [20] could not have done better.

Under the shadow of that great monument to piety, Gresset [21], the author of “Vert Vert,” I am sorry to say, was born, and M. Goblet [22], present Chief Minister, who may have to yield to pressure of bad company, and attempt to break the Concordat with Rome, was a distinguished lawyer, but Peter, the Hermit, the promoter of the first crusade, was born at Amiens; so was Voiture, the great letter-writer, and it is the home of Jules Verne.

It had been running over the leaves of a diary that Edmond and Jules de Goncourt [23], lovers of art in every form, had kept of their thoughts and impressions, and my eyes had fallen upon an entry made July 16, 1856.

“After reading Poe, the revelation of something that critics do not appear to have found. Poe, a new literature, the literature of the twentieth century, the miraculous scientific; imagination by dint of analysis; the making of fabulous tales by A. and B., a literature at once monomaniac and scientific. Zadig, a judge; Cyrano de Bergerac, a pupil of Arago [24]. And things, taking a better part than beings; and love, love lessened in Balzac’s work by money—love yielding its place to other wells of interest; the novel of the future to tell the story of things that are in the brain rather than in the heart of humanity.”

René Goblet. Photograph by Eugène Pirou (coll. Dehs)

|

|

| Edmond and Jules de Goncourt, cartoon by André Gill (1867), (coll. Dehs) | Alexandre Dumas fils, cartoon by Nadar (1848), (coll. Dehs) |

I wondered what Jules Verne, whose first novel appeared in 1862 [sic], would think of that, and I went to Amiens.

His residence is a large, handsome mansion, surrounded by well-kept grounds, in the avenue Charles du Bois [sic], an avenue that commences at the Boulevard du Mail which was an exterior rampart of the old town, and has become the dividing line between old and new Amiens, even as Canal street―that is not wider than the Boulevard du Mail—in New Orleans, is the dividing line between the New Orleans of the colonist, Mr. Cable’s New Orleans, and the New Orleans of to-day.

Jules Verne, who is a Parisian to his fingers’ ends, lives at Amiens because his wife’s relatives are Amiens people. It was his custom to go to Paris once a month for a day or two, until a year ago, when he was wounded by a pistol-shot in the left leg. He limps, cannot bend his leg, and is deprived of other exercise than driving. The nephew, his brother’s son, who fired the shot, was his favorite. No reason could be found for his insanity.

Jules Verne was born at Nantes, in 1828; to be precise, February 8. He wears lightly his fifty-nine years of life. His hair and beard are white, but his face is young, unfurrowed, and there is an expression of frankness in it, and in his clear, calm blue eyes, that always win a heart. Being a Breton, he was born with a profound admiration for the sea; at twelve he had read Robinson Crusoe, and had begun to think of writing stories of shipwrecks.

He studied law, was graduated at the law school, went into the Stock Exchange, not as one of the venerable institution created by an ordinance of Philippe le Bel, but behind the scenes, in it but not of it, like the gulf stream in the ocean.

It has flashed through his mind that he might go to California and seek for a gold mine and find it, and then devote himself to literature; but as he was writing constantly, the Gymnase play-house found something to accept in his mass of manuscripts [25]. It was a comedy in verse, in one act, “Les Pailles Rompues,” and it had been written with Alexandre Dumas fils as a colaborer [sic]. Dumas is his friend. Mark this, for Dumas is not a prodigal of his friendship and is a perfect miser at praising the work of others. I have heard him to say of Jules Verne that if he were a foreigner there would be nothing too good for him in France. Jules Verne says that he has been fortunate in the friendship of Dumas and of his editor, Hetzel, (P. J. Stahl in literature), who coached him, kept him in line, prevented his making excursions in the domain of Balzac [26], ever since the day that his first novel, “Five Weeks in a Balloon,” (“Cinq Semaines en Ballon”), made him able to live by his pen. That was in 1862. Since then he has written fifty volumes—two every year.

Had he caught his inspiration from Edgar Poe, whose influence, in the vivid translations of Baudelaire, has been great on French men-of-letters? Were the impression of the brothers de Goncourt in 1856 similar to his own? Mr. Verne said yes, that he owed much to Edgar Poe and much to Fenimore Cooper, of whom he is an ardent admirer.

His object was to write books that the young could read with profit. He had no pretensions to being a savant, a man of science. He read incessantly. Whenever he was in doubt, he went to one who knew. Joseph Bertrand [27] of the institute had been his adviser on many occasions. He would make errors, perhaps, but not very grave ones. I asked him if his stories were not worked backward, like Gobelin tapestry. He said that he never commenced to write a story without knowing how it was going to end. He writes the plot, then studies the details. The results of his studies are in notes of one word in columns, on sheets of paper, letter size. These words refer to books in his library or to other notes of ideas or facts. When he has become familiar with his notes he writes the story. His manuscript is remarkably neat, on the left side of a letter-size page, leaving a large margin at the right for the dates. [“]Ah! The dates! They give me more trouble than you can imagine. And the names![”] His proof reading costs a good deal of money to the editor, he says. He sends the original manuscript to the printer without an erasure, and there are eight successive proofs to be corrected by him. He is fastidious in the extreme with regard to his style; that has to be absolutely faultless.

Joseph Bertrand, photograph by Pirou (coll. Dehs)

He goes to bed at 8 o’clock, gets up early and is at work until midday, in his cozy work-shop on the second floor, from which we saw a parade and review, by the division general, of the whole garrison. The men march with a swing of the arm that gives them dash and light airiness, something that makes you feel that their heart is in it, or that they would throw it over an obstacle as a rider does, to make his horse leap.

“What made you write ‘North and South?’” I asked.

“Fifty lines out of a few pages of the Comte de Paris’s history of the civil war in America [28]. The Compte [sic] de Paris and I have always entertained pleasant, friendly relations, and I was in sympathy with the North at the time of the war.”

“What material did you use?”

“Everything and anything that I could find [29]. I regret my ignorance of the English language. I have to use translations and translators. The story is interesting because it rests upon alibis, and the key is at the end of the story. I have another work under way. I have thought that there was room for another Robinson. There is “Robinson Crusoe”, “Swiss Family Robinson”, “The Mysterious Island.” The first Robinson is alone, the second has a family, the third is a company of engineers, men of learning. I am writing the story of a boarding school for boys. There are eighteen of them [30]. Fifteen of them are English, two French and one American. I shall place them on a well-fitted yacht that shall be shipwrecked upon an island that is not well known, but that exists—the eldest boy fourteen years of age, the youngest eight. They shall have all the necessary tools to care of [sic] themselves.”

|

|

| The Count of Paris, signed photograph (around 1885) by Numa Blanc fils, Cannes (coll. Dehs) | Another photograph of Philippe d'Orléans, beginning of the 1860s (before his departure to the United States). Photo Caldest Blanford, London (coll. Dehs). |

“I trust you will make the American boy a fine fellow.”

“I always give the Americans my best parts. I have a profound veneration for the American people. I want to see it lauded as it deserves to be. The American boy of the story—to be entitled by the bye “Deux Ans de Vacances” (Two Years’ Vacation)—is to be the practical progressive boy of the party.”

In the hall that leads from the stairway to the work-room is a large chart of the world, a planisphere upon which M. Verne has traced in lines of different colors, the voyages of his heroes.

Cover of the paperback edition of Deux ans de vacances (coll. Dehs)

His entire work, when completed, is to be the amusing description of the earth’s geography.

The historiographer is not a great traveler. His voyages have been “Voyages Autour de Ma Chambre.” [31] He made a trip to New York in 1867 on the Great Eastern and saw the city and Niagara Falls in a week, forsooth! His American friends are like Abraham’s posterity, however, innumerable as grains of sand in the desert, and when the mail carrier brought his letters to him, I volunteered to translate letters of sympathy from a incurable invalid, a girl eleven years old, a boy at Brooklyn public school No. 11, young and old maids and future great men.

To these letters he always replies, though trained to the wiles of a certain Marquis d’Aulnoy [32], who extorted autographs by various pretexts and misrepresentations for the purposes of barter. Jules Verne is acquainted with the coasts of the great countries of Europe, for he has lived some time at sea in his yachts, He took with him to Morocco, in 1878, poor Raoul Duval, who was the apostle in the Chamber of Deputies of a Droite Republicaine, and recently died [33].

|

|

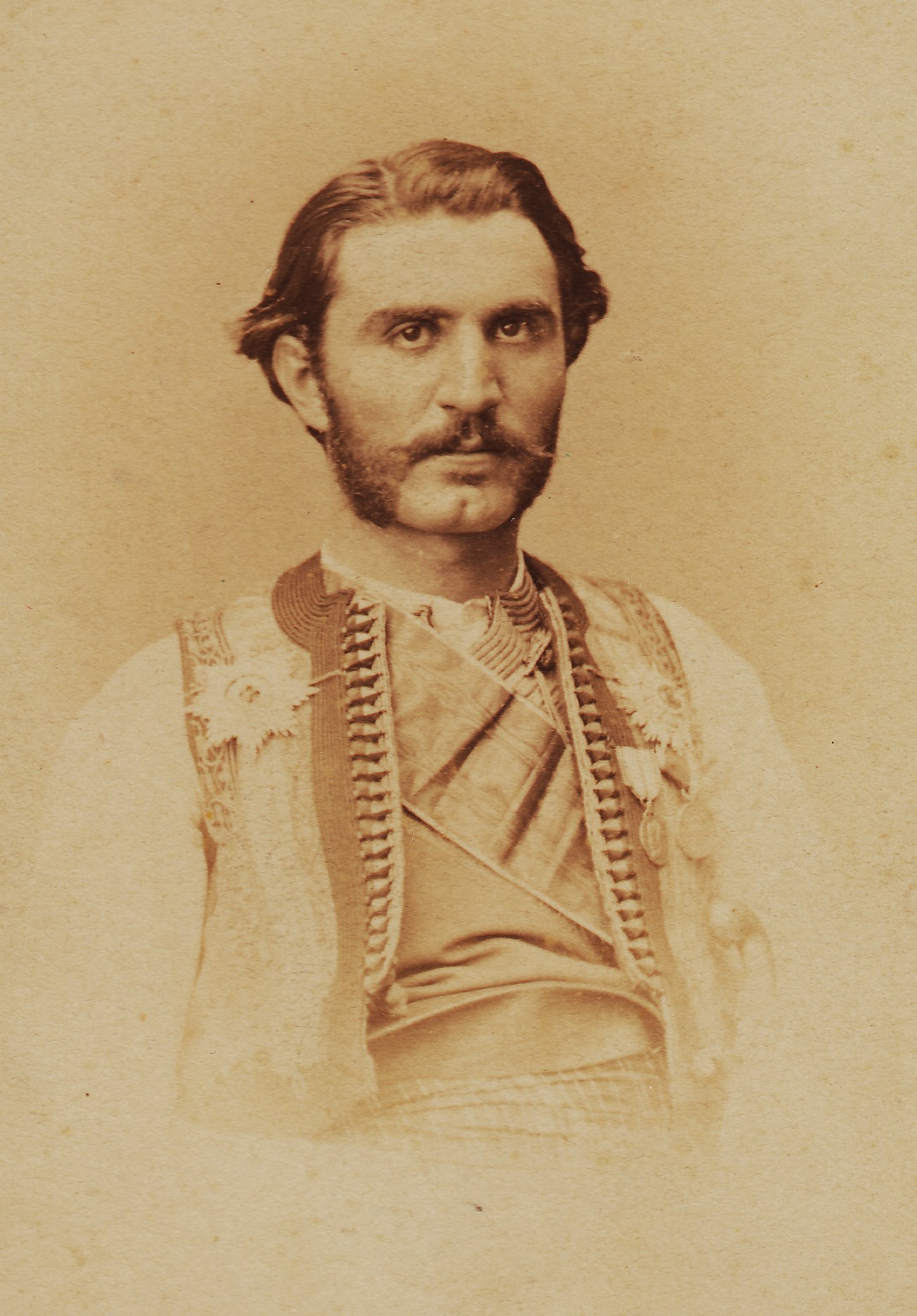

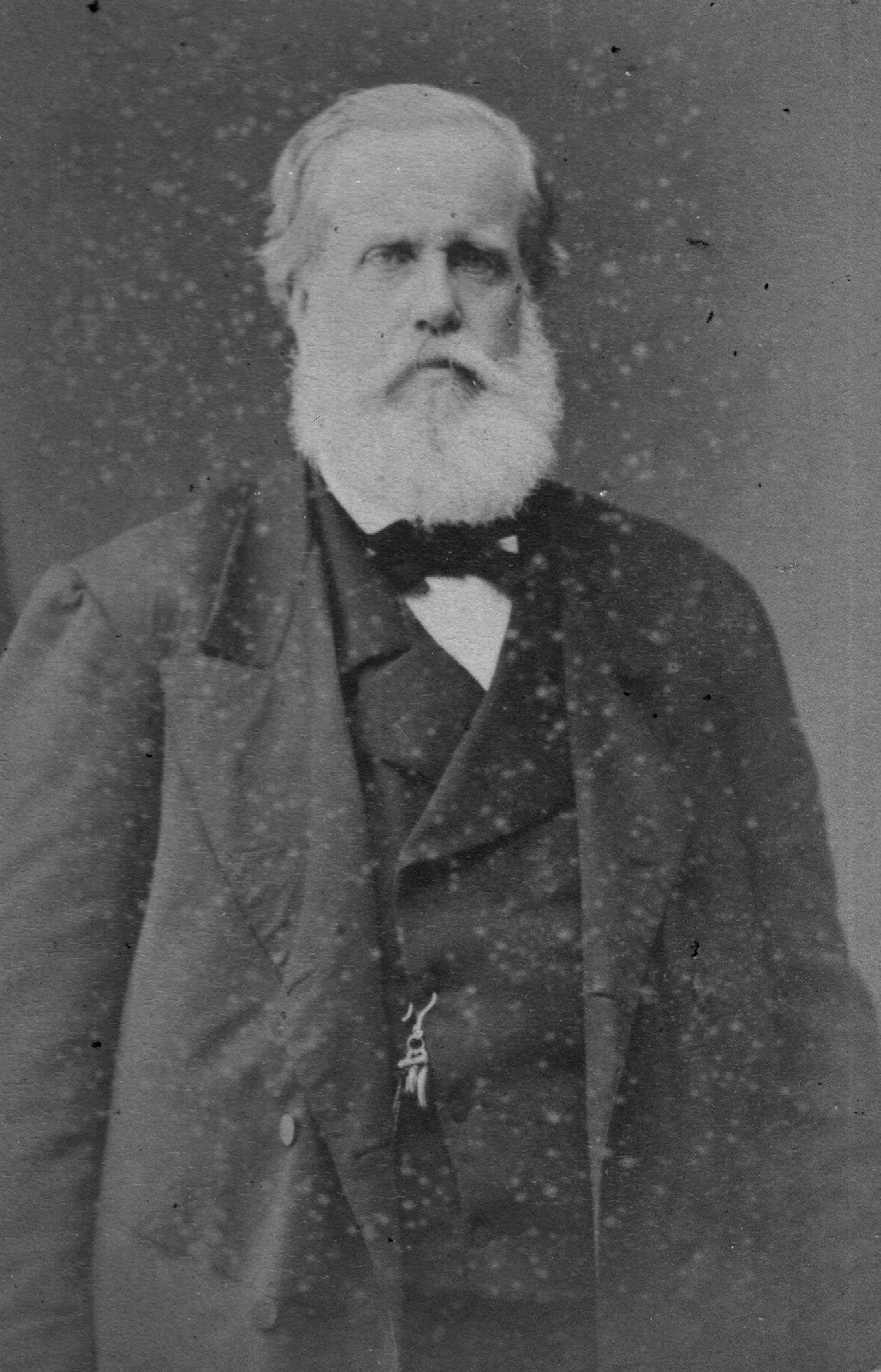

| Raoul-Duval. Unsigned photograph (coll. Dehs) | Nicolas 1st, Prince of Montenegro, photograph by Angerer, Vienna (coll. Dehs) |

His last yacht was sold some time ago to the Prince of Montenegro [34]. It was a steam yacht. The first one was a fisherman’s sail boat of eight or ten tons, where the good Captain Verne’s cabin, five feet by six, was furnished with a vast cupboard containing the books of the vessel, to wit: a few marine charts and three or four ponderous dictionaries and volumes of travels. The crew was composed of two men: Alexander and Alfred [35], one of whom had been through the Crimean war, the other in New Caledonia. Alexander and Alfred had a perfect adoration for Verne; only Alexander never understood how it was possible for so perfect a man to be tainted with so great an infirmity as—lack of love for fishing. Jules Verne is an accomplished pianist, a poet, a novelist, a good critic, a dramatic author, a sailor; “he is,” to quote Hector Malot, “good as gold”—Alexander is right; why is he not a fisherman? Perfection is not of this world.

We went up the stairway to the observatory, wherein the romance writer sits to think of Fergus[s]on, Hatteras, Clowbonny [sic], Plenarvan [sic], Captain Nemo, and as we looked into the cities Amiens and Abbeville, with their winding, narrow lanes, oddly-shaped roofs, belfries, fingers of stone pointing heavenward, and tall, thin poplars, Jules Verne spoke of his love for that land of America—the land of Arabian tales of the future, that is his best wish to see and make known to the world in his tableaux.

HENRI PENE DU BOIS.

View of Amiens. Unsigned photograph, around 1880 (coll. Dehs)

The main contribution of this interview to Vernian scholarship is unquestionably the mention that the source of North Against South can be found in a book about the Civil War written by the Count of Paris (connection already mentioned by Arthur B. Evans [36]).

The Prince Philippe d’Orléans, comte de Paris (1838-1894), grandson of the king Louis-Philippe, was a friend of Jules Verne. He was the Orleanist pretender to the throne of France. It's easy to understand why such a fact became controversial, not only among the family of Jules Verne and the descendants, but also later among Vernian scholars.

In her biography of 1928, Marguerite Allotte de la Fuÿe wrote about the friendship between Jules Verne and the Orléans family without mentioning any political aspect [37]. To avoid any misunderstanding, Raymond Ducrest de Villeneuve (1858-1930), Verne's nephew, thought he should publish a reply to his cousin Marguerite's book. This still unpublished passage shows how much the family was anxious to rid Jules Verne of any suspicion of being a monarchist: [38]

Je crois devoir revenir sur un détail. Jules Verne, au Tréport, fait la connaissance de la Famille d’Orléans. Les Princes d’Orléans, grands lettrés, très instruits, sont des lecteurs fervents de ses œuvres ; ils se passionnent pour ses personnages, et veulent enfin connaître l’homme qui est une des gloires de son Pays. Le Comte et la Comtesse de Paris l’invitent à venir chez eux.

Il s’y rend et y trouve un tel accueil, si affectueux de gens fort simples, qu’il s’y plaît, qu’il y retourne et qu’il se lie d’amitié avec la famille d’Orléans. Les Princes lui ouvrent leurs portes toutes grandes et l’accès d’une intimité qui ne lui laissera que les plus précieux souvenirs.

État-il royaliste ? Je ne le crois pas. Il était avant tout Français, libéral d’instinct et de caractère.

Aussi lorsque plus tard, le gouvernement de la République poussé par des énergumènes, dans la crainte assez chimérique d’une réaction royaliste et plus éventuellement Bonapartiste, édita un décret d’expulsion contre tous les Princes des deux Familles, Jules Verne s’éléva-t-il contre ces mesures absurdes à son avis, inopportunes. […] Il écrivit au Comte de Paris une lettre dont malheureusement nous n’avons pas le double et il reçut de lui une réponse dont j’ai gardé la copie.

Je n’ai donné ces renseignements à l’Auteur du volume qu’après la publication de son livre, car mon Oncle n’aurait pas aimé que ceci fût rendu public. J’ai voulu comme lui que cela restât dans notre Famille, qui, je le souhaite, sera ce qu’était la Famille Verne dont elle est issue, animée des idées les plus libérales, jamais sectaires ni dans un sens ni dans l’autre [39]

I think I'll have to come back to one detail. Jules Verne, in Le Tréport, meets the Orléans Family. The Princes of Orléans, great writers, highly educated, are fervent readers of his works; they are passionate about his characters, and finally want to get to know the man who is one of the glories of his country. The Count and Countess of Paris invite him to come to their home.

He goes there and finds such a warm and affectionate welcome by these very simple people, that he likes it, that he goes back there and befriends the family of Orléans. The Princes opened their doors wide to him and gave him access to an intimacy that would leave him with only the most precious memories.

Is he a royalist? I don't think so. He was above all French, liberal in instinct and character.

So when, later, the government of the Republic, pushed by firebrands, in the rather chimeric fear of a royalist and possibly Bonapartist reaction, issued a decree of expulsion against all the Princes of the two Families, Jules Verne protested against such an absurdity and, in his opinion, inappropriate measures. [...] He wrote a letter to the Count of Paris of which unfortunately we do not have a copy, and he received from him a reply, a copy of which I have kept.

I did not give this information to the Author of the volume until after the publication of her book, for my Uncle would not have liked this made public. Like him, I wanted it to remain in our Family, which, I hope, will remain the Verne Family's position (from which it was originated), animated by the most liberal ideas, never sectarian in one way or another.

Le Tréport, at the mouth of the river La Somme, where Jules Verne's Saint-Michel III had her homeport (postcard, coll. Dehs)

Raymond Ducrest de Villeneuve mentions two letters, one from Jules Verne to the Count of Paris, and the answer he received from the Count. While the answer from the Count of Paris still has to be found, Jules Verne's letter was published by Adrien Carré [40]:

Amiens, 27 Février 1883

Monseigneur,

En souvenir des sentiments que les miens et moi avons toujours professés pour la famille d’Orléans, en souvenir du bienveillant accueil que votre Altesse a daigné me faire personnellement, voulez-vous me permettre de me joindre à tous les hommes de coeur et de bien qui n’ont plus aujourd’hui qu’un devoir et qu’une espérance : le devoir de protester contre l’illégalité, doublée d’une infamie qui vient d’être faite à votre famille, l’espérance qu’un jour viendra où toutes ces injures seront vengées.

En attendant, Monseigneur, veuillez accepter avec tous mes regrets, l’assurance de mon profond respect et de l’inaltérable dévouement qu’a voués à son Altesse son très humble et très respectueux serviteur

Jules Verne

Amiens, February 27, 1883

Monsignor,

In memory of the feelings that my family and I have always professed for the family of Orleans, in memory of the kindly welcome that Your Highness has deigned to give me personally, will you allow me to join all the men of heart and goodness who today have only one duty and one hope: the duty to protest against illegality, coupled with the infamy that has just been done to your family, the hope that the day will come when all these insults will be avenged.

In the meantime, Monsignor, please accept, with all my regrets, the assurance of my profound respect and of the unalterable devotion which your most humble and respectful servant has devoted to his Highness.

Jules Verne

In this letter, Jules Verne was not referring to the law of exile (passed only in 1886), as his nephew believed, but to the prohibition for princes from serving in the army. In 1883, he was considering applying to the French Academy and he asked Alexandre Dumas fils (already member of the French Academy) and Philippe d'Orléans (of whom some relatives were also academicians) to support his candidacy. In 1990, I annotated 27 letters written by Jules Verne to Alexandre Dumas fils [41]. Among many other subjects and issues, Verne discusses in these letters not only his candidacy to the French Academy, but expresses from time to time an opinion about the Orléans family. On July 4 and September 8, he writes:

Je reçois à l’instant votre lettre, et je vous réponds par le courrier. Oui ! la mort du Comte de Chambord doit changer bien des choses, et le nouveau roi m’a toujours témoigné tant de sympathie que sa protection, je pense, ne pourra nous faire défaut. Je venais précisément de lui écrire pour le remercier au sujet de son grand ouvrage sur la guerre civile d’Amérique qu’il vient de m’envoyer [42].

I've just received your letter, and I'll get back to you through the mail. Yes, the death of the Count de Chambord will modify a lot of things, and the new king has always been so sympathetic to me that his protection, I think, cannot fail us. I had just written to him to thank him for his great work on the American Civil War, which he has just sent me.

Si l'événement auquel vous faisiez allusion, s'est produit, si le Comte de Paris est devenu chef de la maison de France, je crains bien que le mauvais vouloir de ces odieux républicains ne rende sa situation extrêmement difficile. Peut-être n'est-ce donc guère le moment de l'entretenir de projets qui me sont purement personnels. [43]

If the event to which you alluded has occurred, if the Count of Paris has become head of the House of France, I fear that the ill will of these odious republicans will make his situation extremely difficult. Perhaps this is not the time, then, to submit to him projects which are purely personal to me.

Philippe d'Orléans, Count of Paris, was considered to be a liberal and literate intellectual, not very inclined to public demonstrations. On June 22, the government of the French Republic passed a law stipulating that « Le territoire de la République est et demeure interdit aux chefs des familles ayant régné en France et à leurs héritiers directs, dans l'ordre de primogéniture » (The territory of the Republic is and remains prohibited to the heads of families who reigned in France and their direct heirs, in the order of primogeniture).

On June 24, 1886, Philippe d'Orléans and his family boarded the ship Victoria and went into exile in England. About 20,000 people gathered in Le Tréport to support the prince on his departure into exile and were invited to sign a kind of guestbook. Le Soleil [44] published anonymously a booklet about this event, including the names of people who attended it.

Jules Verne, whose friendship with the prince was known, is mentioned in the list « des personnes qui se sont rendues au château d'Eu ou au Tréport pour saluer Monseigneur le Comte de Paris avant son embarquement » (of the people who went to the Castle of Eu and to Le Tréport to greet Monsignor the Count before his boarding) [45].

It appears that three and a half months after having been shot in the foot by his nephew Gaston on March 9, 1866 (which left him handicapped), Jules Verne was able to travel from Amiens to Le Tréport. However, no protest from him against being on this list is known. Verne apparently remained in contact with the royal family and in June 1887, he sent a signed copy of the illustrated edition of Robur-le-conquérant to « L'Œuvre de Charité de Madame la Comtesse de Paris » [46].

Castle of Eu, photograph by E. Haglon, Le Tréport, around 1880 (coll. Dehs)

Before 1886, Jules Verne traveled many times between 1878 and 1883/4 to Le Tréport, the port where his Saint-Michel III was anchored at the mouth of the river La Somme. He visited Philippe d'Orléans at the the royal castle of Eu near Le Tréport. There he met, among others, Gaston, Count of Eu (1842-1922), a cousin of the Count of Paris and son-in-law of the King of Brazil, Dom Pedro II of Alcantara (1825-1891) [47]. Jules Verne owed him information about Brazil and sent him a copy of La Jangada on February 4, 1882:

Dans ce livre, Monseigneur, j’ai essayé de peindre, sous la forme romantique [48], un coin de ce merveilleux pays, dont les descriptions m’ont toujours enchanté, et de faire descendre à nos lecteurs ce splendide cours de l’Amazone. Si je suis resté au-dessous de cette tâche, que Votre Altesse veuille bien prendre en considération que je n’ai pu voir que par les yeux des autres ; mais que la série des Voyages extraordinaires m’eût semblé incomplète si je n’y avais fait figurer cette descente du plus beau fleuve du monde. [49]

In this book, Monsignor, I have tried to paint, beneath the romantic form, a corner of this amazing country, whose descriptions have always enchanted me and to allow our readers to follow this splendid course of the Amazon. If I have proved beneath this task, may Your Highness be so kind as to take into consideration that I have been able to see only through the eyes of others, but that the series of Extraordinary Voyages would have seemed incomplete to me if I had not included in it this descent of the most beautiful river in the world.

|

|

| Gaston, Count of Eu (coll. Dehs) | Pedro d'Alcantara, king of Brazil, photograph by Adolphe Braun, Paris (coll. Dehs) |

In September 1861, Philippe d'Orléans and his brother crossed the Atlantic to fight on the side of the Union in the American Civil War. Appointed staff officer of the commander-in-chief of the federal armies, George McClellan, the Count of Paris fought, with his brother, the Southerners at the battle of Gaines' Mill, June 27, 1862.

Back in France, the Count of Paris published a History of the Civil War in America in seven volumes (Histoire de la guerre civile en Amérique, Michel Lévy frères, 1874-1883); the last volume published posthumously). On February 15, 1883, he asked his publishers to send to Jules Verne the first six volumes of this work [50]. This History is one of the sources used by Verne to write North Against South. Verne quotes it in the third chapter of the second part of the novel. One of Verne's handwritten reading notes is dedicated to the Count of Paris' monumental History using keywords to describe every volume [51]. One of those keywords is the name of Doniphan (one of the boys in Two Years' Vacation) in the first volume of the History [52]. The “fifty lines” Verne mentioned as one source of North Against South in the interview still remain to be identified.

Besides furnishing inspiration and documentation to write North Against South, could the Count of Paris have also influenced the setting and the plot of the novel? Indeed, the characters of James Burbank and his son Gilbert, unjustly accused of disloyalty and exposed to the vengeance of their enemies and to the « vociférations » of the « populace » [53], recall the situation in which the princes of Orléans found themselves at the time—at least in Jules Verne's view, who wrote [54] « l’espérance qu’un jour viendra où toutes ces injures seront vengées » (“the hope that the day will come when all these insults will be avenged”). In the unpublished handwritten reading notes is a characterization of the Count of Paris that could also be applied to the Burbanks [55]:

Cte de Paris, instruit, patriote, honnête comme toute sa famille.

Count of Paris, educated, patriotic, honest like all his family.

Burbank and his family live on an estate called “Castle-House”, surrounded by a park:

Cette habitation ressemblait plus à un château fort qu’à un cottage ou une maison de plaisance.

Les salles étaient vastes, les appartements luxueux et superbement aménagés. La famille Burbank y trouvait, au milieu d’un site admirable, toutes les aises, toutes les satisfactions morales que peut donner la fortune, quand elle est unie à un véritable sens artiste chez ceux qui la possèdent [56]

A dwelling looking more a fortified castle than a cottage or a country home.

The rooms were spacious, the living quarters luxurious and superbly furnished. The Burbank family found there, in the midst of an admirable site, all the comfort and moral satisfaction that fortune can give, when it is united with a true artistic sense of those who possess it.

Such a description gives the impression that Jules Verne remembered his memories of the Château d'Eu.

It seems, therefore, that the Vernian novel about the American Civil War hides another conflict―in this case a French one. The hypothesis is by no means risky, as Verne himself had expressed to Hetzel [57]:

D’abord, et c’est ma faute, puisque vous ne l’avez pas compris, Texar et les siens, des forcenés alliés à la populace, c’est la Commune installée à Jacksonville. Ils ont renversé les honnêtes magistrats. Ils ont pris leur place par violence.

First of all, and it's my fault, since you didn't understand. Texar and his people, who were fanatics allied to the populace, comprised the Commune located in Jacksonville. They overthrew the honest magistrates and took their place by violence.

And there is another hidden meaning: North Against South transposits in Florida part of the plot of Verne's « Vendée » novel, Le Comte de Chanteleine (The Count of Chanteleine, 1864), the fight of a “noble” character against his opponents. Hetzel refused in 1879 to include Le Comte de Chanteleine in the Voyages extraordinaires, obviously because of the reactionary political context of the novel [58]. Outraged by the contemporary events surrounding the Orléans family, which he considered of great importance, Jules Verne introduced the substance of one of his former works in a novel apparently dedicated to another political conflict: Texar's Revenge was, in fact, Verne's Revenge.

Notes

- These two reports were published in Entretiens avec Jules Verne 1873-1905, réunis et commentés par Daniel Compère et Jean-Michel Margot (Genève, Slatkine, 1998), pp. 17-22 and 23-29, as well as in Entrevistas con Jules Verne, edited by Ariel Pérez Rodriguez (Marrátxi, Ediciones Paganel, 2018), pp. 19-26 and 27-35. ^

- Often, towards the end of the 19th century, interviews were reproduced (sometimes modified) many times (without being signed) in many American daily newspapers, and it is almost impossible to know which one was the first. In this case, we have irrefutable proof. ^

- Letter to “Monsieur Henri Pène du Bois / 106, Eastern Boulevard / New York / U.S.A.”

Nantes, Musée Jules Verne, B6. ^ - James Gordon Bennett Jr. (1841-1918), was publisher of the New York Herald, founded by his father James Gordon Bennett Sr. (1795–1872), who emigrated from Scotland. Among his many sports-related accomplishments he organized both the first polo match and the first tennis match in the United States, and he personally won the first trans-oceanic yacht race. He sponsored explorations including Henry Morton Stanley's trip to Africa to find David Livingstone, and the ill-fated USS Jeannette attempt to reach the North Pole. He was the model for Gédéon Spilett in Jules Verne's The Mysterious Island. He is also an ancestor of the main character of Michel Verne's short story “In the Year 2889”. ^

- Cyrus West Field (1819-1892) was an American businessman and financier who, along with other entrepreneurs, created the Atlantic Telegraph Company and laid the first telegraph cable across the Atlantic Ocean in 1858, using the Great Eastern to do it. He may have been the model for Cyrus Smith in Jules Verne's The Mysterious Island. ^

- “Jules Verne at Home. The Beginning of His Career as a Writer of Adventure”, in The Quincy Daily Whig (Quincy, IL), July 13, 1887, p. 7. Same article with the same title in Daily Evening Bulletin (Maysville, KY), July 20, 1887, p. 2. A Spanish translation « Jules Verne en caza. El comienzo de su carrera como escritor de aventura », in Entrevistas con Jules Verne, was edited by Ariel Pérez Rodriguez (Marrátxi, Ediciones Paganel, 2018), pp. 36-40. ^

- “Jules Verne”, in Thomas William Herringshaw: The Biographical Review of Prominent Men and Women of the Day, pp. 460-462. Edited

in 1888 by A. B. Gehman & Co.; Boston: B. B. Russel; Chicago: The Lewis

Publishing Co.; Philadelphia: Elliott & Beezley; Philadelphia: W. H. G. Kirkpatrick & Co., etc. Fragments of the interview were published in French in the Bulletin de

la Société Jules Verne n° 131, 1999, pp. 32-33.

Recently, Arthur B. Evans mentioned Herringshaw's book in: “Jules Verne’s American Civil War Novel North Against South”, Extraordinary Voyages. The Newsletter of the North American Jules Verne Society, inc. Vol. 25, No 2, Spring/Summer 2019, pp. 1-5. ^ - Charles Sotheran: [Introduction] in The Library and Art Collection of Henry de Pene du Bois, of New York. New York: George A. Leavitt and Co., June 1886, p. ii. ^

- Jules Verne: Dr. Ox’s Experiment. Illustrated by William Pène du Bois. Biographical introduction by Willy Ley. Epilogue by Hubertus Strughold. New York: The MacMillan Company, 1963. William Pène du Bois also wrote the full-length Verne pastiche The Twenty-One Balloons (1947); his own biographical note in that edition of Dr Ox (p. 101) makes the Verne connection clear. ^

- https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/ ^

- On Sundays, like July 3, 1887, The Indianapolis Journal carried the title The Sunday Journal. ^

- Jules Verne and Adolphe d'Ennery: Around the World in 80 Days. The 1874 Play. Albany (GA), BearManor Fiction, 2012, 178 p. This volume (North American Jules Verne Society's Palik series, No 6), with an introduction by Philippe Burgaud, Jean-Michel Margot, and Brian Taves, reproduces a rare archival copy of an exact translation of the original Verne-d'Ennery play, prepared for the Kiralfy brothers and copyrighted by them. As a publication, it received very limited distribution. Some modifications to the text were made by the Kiralfys before it was finally presented on the American stage. ^

- Arthur B. Evans : “Jules Verne’s English Translationsˮ. Science Fiction Studies 32.1, March 2005, p. 105-142 (North Against South is mentioned on p. 130-131). ^

- Brian Taves & Stephen Michaluk, Jr.: The Jules Verne Encyclopedia. Lanham (MD) & London, Scarecrow Press, 1996, 258 p. Editions of North Against South are presented on p. 172-173. ^

- Robert H. Sherard: “Jules Verne at home. His own account of his life and workˮ. McClure's

Magazine, vol. II, no 2, January 1894.

Marie A. Belloc : “Jules Verne at homeˮ. The Strand Magazine, vol. IX, February 1895. ^ - Adrien Marx: « Indiscrétions parisiennes. Jules Verne ». Le Figaro, February 26, 1873. Translated into English, this

article is the “Introductionˮ of Verne's novel Around the World in 80 Days, published by Porter & Contes and James Osgood and Company.

Charles Raymond: « Les célébrités contemporaines. Jules Verne ». Musée des Familles, vol. 42, no 9, September 1875, p. 257-259.

Jules Claretie: « M. Jules Verne ». In: Portraits contemporains, Polo (Paris), vol. 2, 1875, p. 211-224. ^ - Eugène Viollet-le-Duc (1814-1879), architect whose specialty was the restoration of Middle Ages buildings, controversial activity at that time and very criticized by the British John Ruskin. Hetzel asked Viollet-le-Duc to enlarge his country residence « Bellevue » in Sèvres. Hetzel published several of Viollet-le-Duc's books between 1874 and 1879. ^

- It looks like a quote from French historian Jules Michelet (1798-1874). Connected to the Middle Ages, the idea of “sculptured prayers” was common at the end of the nineteenth century, in Europe and in America. Theodore Parker (1810-1860) preached on January 4, 1846 in Boston, mentioning “the prayers of a pious age done in stone”. ^

- John Ruskin (1819-1900) was a leading English art critic, a leader of the Pre-Raffaelite movement and a supporter of William Turner. ^

- Heinrich Gottfried Ollendorff (1803-1865) was a German grammarian and language educator. Ollendorff's texts use artificially constructed sentences, which, while illustrating grammar and tense well enough, are extremely unlikely to occur in real life. Mark Twain ridicules Ollendorf's sentences—questions in particular—for just that quality. ^

- Jean-Baptiste-Louis Gresset (1709–1777) was a French poet and dramatist, best known for his poem Vert-Vert. ^

- René Goblet (1828-1905), republican politician, former district attorney general and mayor of Amiens and representative of the Somme. With Frédéric Petit he founded in 1869 the republican progressive newspaper Le Progrès de la Somme. Frédéric Petit became mayor of Amiens in 1880, and it's with him that Jules Verne was town commissioner of Amiens. ^

- The brothers Jules (1830-1870) and Edmond (1822-1896) de Goncourt were novelists of the naturalist school, best known for their Diary (Mémoires de la vie littéraire), covering the years 1851 to 1896), which Edmond published in 9 volumes between 1887 and 1896. This publication, although toned down, scandalized the contemporaries who were denounced and ridiculed; Jules Verne was spared by their comments, Hetzel criticized for denying to Huysmans any talent. The paragraph quoted here is in the first volume (G. Charpentier et Cie, 1887), pp. 137-138. ^

- The Goncourts refer here to a Voltaire short story « Zadig ou la destinée » (1747) and to François Arago (1786-1853), rather than to his brother Jacques (1790-1854), who was a friend of Jules Verne. ^

- Error often reproduced in articles of that time: Jules Verne's first play was staged in 1850 at the Théâtre Historique but was repeated several times between 1853 and 1872 at the Théâtre du Gymnase-Dramatique. ^

- Possible reference to Paris in the Twentieth Century, a novel which was turned down by Hetzel in 1863. ^

- Joseph Bertrand (1822-1900), a scientist close to Hetzel. ^

- Louis Philippe Albert, Count of Paris (1838-1894), an Orleanist pretender to the throne of France. ^

- Besides the works by the Count of Paris, Verne knew Histoire de la guerre civile américaine 1860-1865 by Louis Cortambert and F. de Tranaltos (Amyot, 1867, 2 vols), book he presented on March 20, 1868 to the Geographical Society of Paris. ^

- For the definitive publication, Jules Verne reduced their number to fifteen, including the ship's boy Moko. ^

- Title of a book published in 1794 by Xavier de Maistre (1763-1852), mentioned among others by Verne in The Green Ray. ^

- This name is not precise enough to be tracked down with accuracy. ^

- Edgar Raoul-Duval (1832-1887), son of a politician, born in Amiens and temporarily settled in Nantes, was a close friend of Gustave Flaubert (as evidenced by their published correspondence) and Hetzel. He was the owner of the castle of Montcalm (Aude) which Jules Verne transported in 1889 to Canada in Famille-sans-nom (Family Without A Name). ^

- Nicolas I (1841-1921), prince of Montenegro since 1860 and king from 1910. He bought the Saint-Michel in 1886, renamed her Sybila and sold her in 1891. ^

- Alexandre Delong (1831-1900) and Alfred Berlot. These details as well as the quotation from Malot (which follows) seem to be taken from the booklet Jules Verne by Jules Claretie (Paris, A. Quantin (coll. Les célébrités contemporaines), 1883, 32 p., mainly from the pages 14-18). ^

- See note 7. ^

- Marguerite Allotte de la Fuÿe. Jules Verne, sa vie, son œuvre. Paris, Simon Kra, 1928, 294 p. The reference to the Orléans family is

on page 210.

English translation: Margurite Allotte de la Fuÿe. Jules Verne. London, Staples Press Ltd., 1954, 222 p. ^ - Even despite the fact that in Verne's handwritten notes (yet to be studied and published) can be found this word as peremptory as it is

condensed: « moinarchiste » (Amiens, Bibliothèques Amiens Métropole (Metro Area Libraries), collection Jules

Verne, MS JV 22, fol. 7).

The word « moinarchiste » is not a writing mistake, but a pun―kind of wordplay Verne was used to—combining « moi » (I) and « monarchiste » (monarchist). ^ - R. Ducrest de Villeneuve. Mémoire sans titre (Memoir Without Title). Former collection of the Centre International Jules Verne, n° 20283 (copy), pp. 108-109. The original of this document can be found in the collection of the Musée Jules Verne, Nantes (B233). ^

- This document is available at the French National Archives (300 AP III, fol. 589). See the well-documented article by Adrien Carré : « Jules Verne et les Princes d’Orléans », in Bulletin de la Société Jules Verne, no 53 (1980), pp. 164-172 ; reprinted later in Bulletin de la Société Jules Verne, no 164 (2007), pp. 42-49. ^

- Volker Dehs. « Vingt-sept lettres inédites de Jules Verne à Alexandre Dumas fils ». Bulletin de la Société Jules Verne, no 94 (1990), pp. 10-33. ^

- Letter #5 (July 4, 1883) published in Bulletin de la Société Jules Verne, no 94 (1990), p. 14. The Count of Chambord died on August 24, 1883. ^

- Letter #8 (September 8, 1883) published in Bulletin de la Société Jules Verne, no 94 (1990), p. 16. ^

- Le Soleil (The Sun) was a French daily newspaper. It was founded in 1873 and run by the journalists Édouard Hervé and Jean-Jacques Weiss. Le Soleil was a monarchist daily, more moderate than others, and sold for five centimes at the end of the nineteenth and start of the twentieth century. It was one of two French newspapers that gave the best coverage of international news, along with Le Temps (wikipedia). ^

- Anonymous : Le Départ pour l’Exil. Eu-Tréport, June 24, 1886, 60 p. The list fills up pages 46 to 60. This booklet was probably sponsored by the royal family, available at gallica.bnf.fr. ^

- Item #30443P for sale by Peter L. Stern & Company, Inc., Boston, at a price of $12,500 (https://www.sternrarebooks.com/pages/books/30443P/jules-verne/robur-le-conquerant). ^

- Dom Pedro was overthrown by a coup in 1889, among other things, for having abolished slavery in his country. He took refuge with his wife in Paris where he died. This detail is undoubtedly anecdotal and has no real connection with the plot of North Against South. However, Jules Verne paid him a posthumous homage through the character of the King of Malécarlie in Propeller Island (1895). ^

- Possibly a reading error, which could be replaced by « romanesque ». ^

- Georges Raeders: « Une lettre inédite de Jules Verne », in J.-M. Massa (éd.): La Bretagne, le Portugal, le Brésil : Échanges et rapports. Université de Nantes, vol. I, 1977, p. 433. ^

- Mentioned by Jean-Yves Mollier: Michel & Calmann Lévy ou la naissance de l’édition moderne 1836-1891. Calmann Lévy, 1984, p. 461. ^

- Bibliothèques d’Amiens Métropole, collection Jules Verne, JV MS 23 (Fiches de lecture), no 13 (26.7 x 21 cm). The reading notes about North Against South are ordered just under the title Le Chemin du Pays, temporary title of the novel Le Chemin de France (The Road to France, 1887), which Verne began to write in 1886, right after North Against South, written between July 1885 and Spring 1886. ^

- Alexander William Doniphan (1808-1887) was a 19th-century American attorney, soldier and politician from Missouri who is best known today as the man who prevented the summary execution of Joseph Smith, founder of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, at the close of the 1838 Mormon War in that state (Wikipedia). ^

- Alexander William Doniphan (1808-1887) was a 19th-century American attorney, soldier and politician from Missouri who is best known today as the man who prevented the summary execution of Joseph Smith, founder of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, at the close of the 1838 Mormon War in that state (Wikipedia). ^

- See note 40. ^

- Bibliothèques d’Amiens Métropole, collection Jules Verne, JV MS 22 (Fiches de travail), fol. 20. ^

- Nord contre Sud, part 1, chapter 2. ^

- Letter written to Hetzel on October 15, 1885. Correspondance inédite de Jules Verne et de Pierre-Jules Hetzel, tome III. Genève, Slatkine, 2002, p. 324. About unexpected references of the Commune in Verne novels, see my article « Les Voyages extraordinaires en face de La Débâcle ». Bulletin de la Société Jules Verne, no 80, 1986, pp. 25-31. ^

- Brian Taves, “Verne’s Forgotten, Youthful Swashbucklerˮ, Verniana, vol. 3, 2010-2011, pp. 33-50, article reproduced in Edward Baxter's translation, The Count of Chanteleine. A Tale of the French Revolution. BearManor Fiction, 2011, pp. 1-24 (The Palik Series, 4). ^