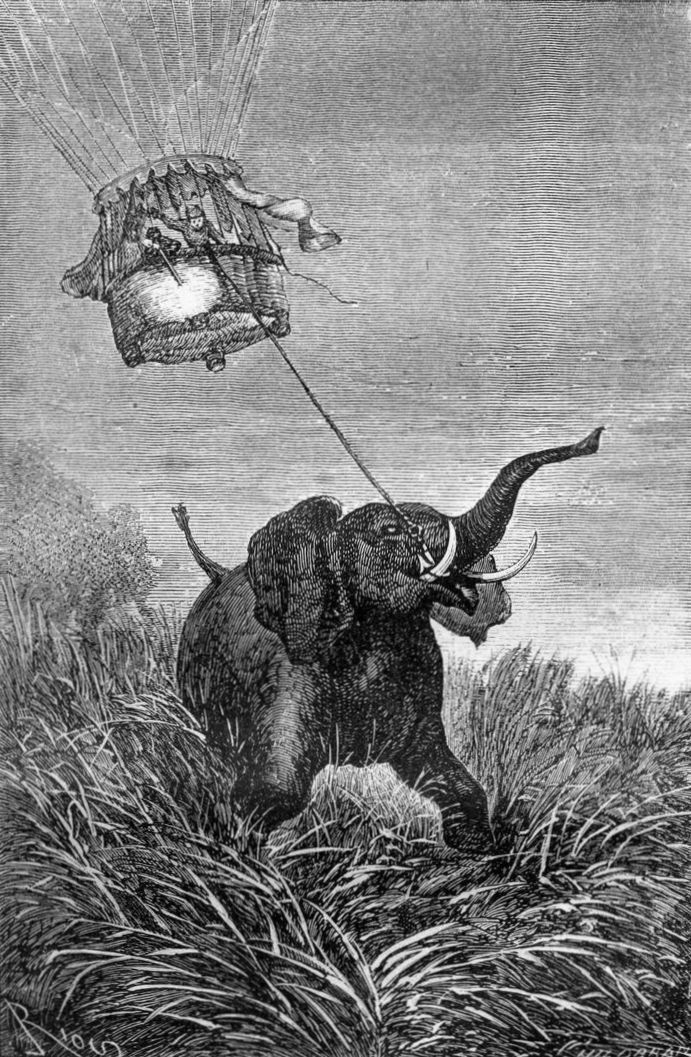

In a memorable episode in Chapter XVII of Jules Verne’s Cinq semaines en ballon (1863, Five Weeks in a Balloon), the protagonists’ balloon inadvertently snags an elephant, and they are towed for nearly an hour and a half across the African savanna. In Chapter XXIX of the same novel, a similar possibility using camels is briefly discussed:

|

|

— Est-ce que nous sommes toujours dans le pays des nègres, Monsieur Samuel?

— Toujours, Joe, en attendant le pays des Arabes.

— Des Arabes, Monsieur, de vrais Arabes, avec leurs chameaux?

— Non, sans chameaux; ces animaux sont rares, pour ne pas dire inconnus dans ces contrées; il faut remonter quelques degrés au nord pour les rencontrer.

— C’est fâcheux.

— Et pourquoi, Joe ?

— Parce que, si le vent devenait contraire, ils pourraient nous servir.

— Comment ?

— Monsieur, c’est une idée qui me vient: on pourrait les atteler à la nacelle et se faire remorquer par eux. Qu’en dites-vous ?

— Mon pauvre Joe, cette idée, un autre l’a eue avant toi; elle a été exploitée par un très spirituel auteur français1 (note 1: M. Méry) ... dans un roman, il est vrai. Des voyageurs se font traîner en ballon par des chameaux; arrive un lion qui dévore les chameaux, avale la remorque, et traîne à leur place; ainsi de suite. Tu vois que tout ceci est de la haute fantaisie, et n’a rien de commun avec notre genre de locomotion.

Joe, un peu humilié à la pensée que son idée avait déjà servi, chercha quel animal aurait pu dévorer le lion; mais il ne trouva pas et se remit à examiner le pays.

“Are we still in the negro country, doctor?”

“Yes, and on our way to the country of the Arabs.”

“What! real Arabs, sir, with their camels?”

“No, not many camels; they are scarce, if not altogether unknown, in these regions. We must go a few degrees farther north to see them.”

“What a pity!”

“And why, Joe?”

“Because, if the wind fell contrary, they might be of use to us.”

“How so?”

“Well, sir, it’s just a notion that’s got into my head: we might hitch them to the car, and make them tow us along. What do you say to that, doctor?”

“Poor Joe! Another person had that idea in advance of you. It was used by a very gifted French author—M. Méry—in a romance, it is true. He has his travellers drawn along in a balloon by a team of camels; then a lion comes up, devours the camels, swallows the tow-rope, and hauls the balloon in their stead; and so on through the story. You see that the whole thing is the top-flower of fancy, but has nothing in common with our style of locomotion.”

Joe, a little cut down at learning that his idea had been used already, cudgelled his wits to imagine what animal could have devoured the lion; but he could not guess it, and so quietly went on scanning the appearance of the country. (trans. William Lackland, 1869)

Who is this M. Méry mentioned in the note at the bottom of the page in the original French edition and inserted into the text of the English translation? Whoever he was, he seems to have been the literary source for both these episodes in Cinq semaines en ballon.

Thanks to Elliot Hughes, a young PhD student in physics at Rutgers University, we now have an answer. On November 11, 2012, Elliot contacted me about this reference in Cinq semaines and asked if I knew who M. Méry might be. After consulting a couple of encyclopedias (and the Bibliothèque Nationale through its excellent website at Gallica.bnf.fr), I finally located the author in question: Joseph Méry (1798-1856), a relatively well-known French poet and novelist from the first half of the nineteenth century. Ironically, my efforts to discover his identity proved to be rather superfluous—Méry has his own page (in French and English) in Wikipedia, and a simple Google keyword search would no doubt have pointed me to him.

In any event, I communicated this information to Elliot, and he did some additional research on Méry’s oeuvre and discovered the work that features this passage. It first appears in Méry’s 1844 story La pêche au lion (Fishing for Lion), a story that was reprinted in several subsequent collections by Méry (Un mariage de Paris [1873], Une conspiration au Louvre [1890], etc.). Here is what it says:

Tarde venientibus ossa! telle fut la réflexion que parut faire ce roi des animaux devant le dernier fragment du squelette. Il y avait pourtant encore un morceau assez délicat; c’était la ceinture de cuir de boeuf à laquelle était attaché le crochet de fer. La Fontaine a dit: « Les loups mangent gloutonnement; » qu’aurait-il dit des lions ? Celui-ci, alléché par l’odeur, se précipita sur la ceinture de cuir de boeuf et l’avala gloutonnement. Une vive secousse ébranla l’aérostat. L’animal avait englouti dans sa poitrine le crochet de fer, et ses bonds furieux attestaient des douleurs au-dessus des forces léonines. Le ballon, depuis si longtemps stationnaire, s’agitait convulsivement, mais sans direction fixe. Il flottait au hasard, selon le caprice de son conducteur étranglé. [...]

Belzoni prit la corde et la secoua fortement, comme un pêcheur qui sent que le poisson a mordu sur l’appât. Le lion poussait des rugissements d’agonie et se débattait avec les derniers efforts de sa vigueur. Un râle suprême retentit dans la solitude, et le monstre retomba de tout son poids de cadavre sur le sable, en communiquant au ballon un mouvement de descente très-vif.

— Et maintenant, dit Belzoni, aidez-moi tous deux; nos six mains à la corde, et de l’ensemble surtout.

L’espoir de salut doubla les forces des voyageurs. Belzoni, vigoureux comme un funambule, et habitué aux manoeuvres de chanvre roulé, tenait la place de deux chevaux remorqueurs. Le lion s’élevait majestueusement à chaque effort de six mains unies, et, quand il fut arrivé à fleur de la nacelle, Belzoni lui coupa les quatre pattes et quelques filets succulents; puis, abandonnant le reste aux vautours, il dit à M. Hogges :

— Le vent souffle vers Eléphantine; nous allons dîner avec notre pêche, et nous coucherons ce soir sous les huttes d’Assouan.

Tarde venientibus ossa! [he who arrives late gets only the bones], such was no doubt the thought that was on the mind of this king of the jungle as he stood in front of this last fragment of skeleton. There was however one last tasty piece left on it: it was the camel’s belt made of cow leather to which was attached the [balloon’s] iron hook. La Fontaine once said “Wolves eat gluttonously;” what would he have said about lions? The lion, attracted by the smell, rushed up to the leather belt and gobbled it down greedily. A sudden jerk shook the aerostat. The animal had swallowed the iron hook, and it was now jumping about furiously in great pain. The balloon, which has been stationary for quite some time, now moved convulsively, bobbing here and there. It was being pulled in random directions, following the tortured leaps of the captive animal. [...]

Belzoni took the line and yanked on it very hard, like a fisherman who hooks a fish that has taken the bait. The lion roared with agony and struggled mightily against the line to the last of its strength. But it was not long before a final roar echoed through the air and the monster fell dead upon the sands, pulling down the balloon one last time.

“And now,” said Belzoni, “the two of you must help me! All six hands on the rope and let’s pull together!”

The hope of saving themselves doubled the strength of the travelers. Belzoni, who was as vigorous as a gymnast and accustomed to handling tightropes, pulled on it like two draft horses. As a result of those six hands working together, the lion rose majestically into the air and soon reached the balloon’s basket. Belzoni cut off its four legs and a few succulent steaks from its body, leaving the rest for the vultures. He then said to M. Hogges:

“The wind is blowing toward Elephantine. Tonight, we’ll dine on our catch and sleep in the huts of Assouan” (trans. ABE).

Congratulations to our young colleague who dug up this intertextual jewel which adds to our understanding of the literary sources of Verne's Voyages extraordinaires. Bravo!