There is a rich tradition of Jules Verne adaptations produced or co-produced in the Spanish language. From Spain came MATHIAS SANDORF / EL CONDE SANDORF / IL GRANDE RIBELLE (France/Spain/Italy, 1962), THE LIGHT AT THE EDGE OF THE WORLD / LE PHARE DU BOUT DU MONDE / LA LUZ DEL FIN DEL MONDO / IL FARIO IN CAPO AL MONDO (US/France/Spain/Italy, 1971), UN CAPITAN DE QUINCE ANOS / UN CAPITAINE DE QUINZE ANS (Spain/France, 1972), LA ISLA MISTERIOSA / L'ILE MYSTERIEUSE / L'ISOLA MISTERIOSA E IL CAPITANO NEMO / THE MYSTERIOUS ISLAND OF CAPTAIN NEMO (Spain/France/Italy, 1973, television mini-series and feature version), VIAJE AL CENTRO DE LA TIERRA / THE FABULOUS JOURNEY TO THE CENTER OF THE EARTH / WHERE TIME BEGAN (1977), NEMO (1979), MISTERIO EN LA ISLA DE LOS MONSTRUOS / MONSTER ISLAND / MYSTERY OF MONSTER ISLAND (Spain/US, 1981), and LOS DIABLOS DEL MAR / SEA DEVILS (1982). LOS SOBRINOS DE CAPITAN GRANT was brought to the screen in 1969 as a movie and television and for television again in 1977, both times based on the zarzuela from the novel. Note: Capitalized titles are for movies, italicized are for books. So, La Jangada is a book, LA JANGADA is a movie.

Other films in the Spanish language, and among the very best interpretations of Verne to the screen, have come from Mexico. These include MIGUEL STROGOFF, EL CORREO DEL ZAR (1943), DOS ANOS DES VACACIONES / SHIPWRECK ISLAND (Spain/Mexico, 1960), and EIGHT HUNDRED LEAGUES OVER THE AMAZON / 800 LEGUAS POR EL AMAZONAS / LA JANGADA (1960). VIAJE FANTASTICO EN GLOBO / FANTASTIC BALLOON VOYAGE / THE VOYAGE / FIVE WEEKS IN A BALLOON (1975) is the only one of the four screen versions of the novel to actually tell Verne’s story, and does so magnificently. In 1993, EIGHT HUNDRED LEAGUES DOWN THE AMAZON emerged as a Peruvian - United States co production, but could not match the magnificent spectacle of the 1960 version.

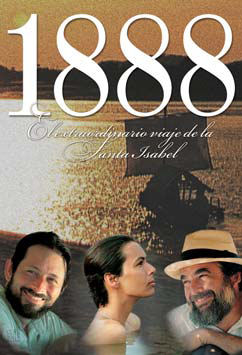

Here is a rich alternate strain distinct from that of Hollywood. Rather than looking to Verne for another “blockbuster,” the author’s own novels of the region have sometimes served as a starting point, as in bringing La Jangada (1881) to the screen, and now Le Superbe Orénoque (1898). In this the Latin American cinema has now made a major new contribution. 1888–EL EXTRAORDINARIO VIAJE DE JULES VERNE (initially entitled 1888–EL EXTRAORDINARIO VIAJE DE SANTA ISABEL) is a meditation on Le Superbe Orénoque, Verne’s life, and much more. This Cine Seis Ocho/Centro Nacional Autonomo de Cinematografia production was the official Venezuelan entry for the 2005 Academy Award for Best Foreign Film, and is now available on DVD.

1888–EL EXTRAORDINARIO VIAJE DE JULES VERNE opens with Honorine Verne (Elba Escobar) and her husband, a Latin-looking and bearded Jules (Marco Villarubia), quarreling over his determination to travel to the Orinoco River, to gain local color for a novel. He assures her his only mistress is adventure. And, as she points out, he is aging; it may be his last chance to journey to America.

He meets Count Stradelli (Ronnie Nordenflycht) and joins him on a boat trip up the Orinoco to learn its source. Stradelli and Verne encounter Jean Dekermore, riding away from bandits, and who is saved by Verne’s rifle fire. Dekermore joins them on the expedition, and explains that he is 17 and searching for his father, lost in this region years before when he had mistakenly believed thought wife and son killed in a shipwreck. Despite the likelihood of his father’s death in the intervening years, Dekermore refuses to believe that he is not still alive.

1888–EL EXTRAORDINARIO VIAJE DE JULES VERNE emphasizes the travelogue aspects of the novel, highlighted by authentic Venezuelan locations. There are abundant didactic touches revealing the Orinoco that further emulate the flavor of Le Superbe Orénoque and Vernian fiction generally. The melodramatic dangers along the river that the novel had provided are minimized or deleted entirely. The result is a filmic travelogue and character study that comes to define adventure as internal revelation as much as external incident. For Alfredo Anzola, who produced and directed and cowrote the script with Gustavo Michelena and Rafael Arraiz Lucca, Verne is an entirely different type of inspiration than generally found in Hollywood. To underline this distinction, legends of gold hidden atop mountains and elsewhere are mentioned but bypassed by the explorers, seeking instead, as described by Verne in the film, the gold in the human heart. By contrast, a Hollywood version would have found a treasure hunt an irresistible sidelight.

The structure of Le Superbe Orénoque is a variation on two novels Verne had written nearly three decades earlier. In Les Enfants du capitaine Grant teenage Mary Grant, together with her younger brother, initiate an around-the-world trek in search of their missing sea captain father. In Les Forceurs de blocus, “John,” joining the Dolphin as an apprentice with her “uncle,” proves to be Jenny Halliburt, determined to persuade the captain to aid her aim of rescuing her imprisoned abolitionist father at the voyage’s destination, Charleston. However, Jeanne de Kermor travels in disguise as a young man for half the novel, again with a friend of her father as supposed uncle, whereas in Les Forceurs de blocus the disguise is brief. Mary was only one of many leading characters in The Children of Captain Grant, and she never sacrificed her femininity. Hence, even considering Jenny and Mary, the Jeanne of Le Superbe Orénoque is one of Verne’s most vivid and proactive literary heroines, like the Nadia of Michel Strogoff, but alone of these, Jeanne elicits a response from the hero of Le Superbe Orénoque that is not only emotional but sexual. And it is this more modernist dimension of the novel, the interest in gender roles, that 1888–EL EXTRAORDINARIO VIAJE DE JULES VERNE delineates.

1888–EL EXTRAORDINARIO VIAJE DE JULES VERNE boils down the novel’s numerous characters to a trio in the interest of exploring the psychology of each and using the mystery of Dekermore’s gender as a vehicle to explore an unusual love triangle. Both Verne and Stradelli take the place of the novel’s Jacques Helloch, dividing his role of ingenue, explorer, hero, and lover.

Both Stradelli and Dekermore are thrilled to meet Verne and attest that they have read all of his books. While in some ways idealized, Verne is also reimagined, although retaining many biographical facts. He tells Dekermore that he was shot in the leg by a madman for monetary reasons. When Verne dives into the river to save Dekermore, she remarks that he is as heroic as one of his own characters.

Similarly, Ermanno Stradelli (1852-1926) is also an actual explorer. Hence, in the film both the principal male figures are historical personages, myth and legend blending in a fanciful love story set against a background of exploration, mixing actual deeds (Stradelli) with fictional ones (Le Superbe Orénoque). The result is also patriarchal: masculinity is real, and femininity, whether the female gender or the anxiety that possible homosexual attraction induces, serve primarily to define masculinity and actuality, since Dekermore is the one fictional character who sets into motion the dynamic between Verne and Stradelli.

As enacted by the androgynous, unglamourous Kristin Pardo, Dekermore is initially credible in disguise as a woman pretending to be a young man. From the outset, Stradelli finds Dekermore’s motives entirely too melodramatic to be credible, remarking that it sounds more like a Verne story than truth. Indian natives who visit the travelers asking for tobacco at once realize Dekermore’s gender, but the whites believe they have ignorantly made a mistake.

Then Verne spies Dekermore undressing to swim, and moments later he must save her when she is bit by an eel. From the Indian’s intuition, and remembering reading in the newspaper years ago of the shipwreck and disappearance of Dekermore, Verne had already guessed her gender. She asks him to keep it secret from Stradelli.

The sexual overtones that probably precluded a contemporary English-language publication Le Superbe Orénoque at the time of its initial publication in 1898 (it was published in Spain as El soberbio Orinoco and finally appeared as The Mighty Orinoco in the United States in 2002) thus become the basis of the film. Stradelli calls Dekermore “boy” rather than by his name, Jean, as a way of affirming his belief in Dekermore’s gender and the gulf it creates between them. Stradelli’s frustration at his attraction toward Dekermore, dreaming of making love to the person he believes is another man, leads him to become increasingly ill-tempered. He visits an Indian for information on the river, and in his absence Dekermore reveals herself in a dress to fulfill Verne’s wish, and with the dropping of pretense the two consummate their growing love.

Stradelli, unable to cope with his own passions, senses the new link between Verne and Dekermore. Stradelli accuses them of the same homosexual alliance that he fears will be the result of his own passion for Dekermore. She responds by indicating that she is aware that the Frenchman Chaffanjon purportedly has already discovered Stradelli’s goal, the source of the Orinoco.

With the trio now alienated from one another, Dekermore departs in the rowboat on her own, and is found the next day barely alive. Stradelli had been reluctant to detour the expedition to stop at the Mission Santa Juana, as recommended by the Indian as the best source for information on Dekermore’s father. Stradelli agrees to go to the Mission, and that even geography takes second place to finding a missing father.

From the book, photography becomes a central motif of the movie, and 1888–EL EXTRAORDINARIO VIAJE DE JULES VERNE recognizes its own role in sharing the medium. Verne prophecies that it will come to supplement human memory in the future. Taking photographs of Dekermore alongside the verdure, Stradelli realizes he is beginning to fall in love with Dekermore, which he finds utterly inexplicable.

Photographs also provide the final traumatic revelation for Stradelli as to Dekermore’s true gender. Just as the image itself has already hinted at, then revealed this fact first to the audience, then to Verne, it is while Verne is photographing Dekermore splashing and emerging naked from the river that Stradelli first fully sees her. At first he is overwhelmed, stalking off, then haunted by the memory of her moving amidst the water.

1888–EL EXTRAORDINARIO VIAJE DE JULES VERNE uses the androgyny of Verne’s heroine as a way to metaphorically explore the source of sexual identity that parallels the journey to the source of the Orinoco. As the role of still photography to record the journey indicates in the movie, especially with the androgynous motif, a motion picture of Le Superbe Orénoque cannot simply be a straightforward adaptation. The motion picture camera would reveal far more rapidly the guise that the Vernian prose narrative could conceal. Hence, it is inherently more appropriate for the film to examine the nature of this shift, and its impact on others, emphasizing its impact on fewer but deeper characters. Narrative shifts and reinterpretation are essential to relating the story in a visual medium. The search for the source of a river becomes equally the exploration of the source of the movie, the meaning of Le Superbe Orénoque.

While some might criticize the film as exploitive for drawing Verne into the affair with Dekermore, in fact it is necessary to explore his character and as part of the journey of 1888–EL EXTRAORDINARIO VIAJE DE JULES VERNE into how love affects two divergent men. When Stradelli sees a mountain he must measure its height, while Verne is content with its magnificence. Stradelli explains that he needs truth, while Verne, the writer, can live with lies. Yet Stradelli also wants to be swallowed by nature, as he puts it, while Verne, for his part, reckons himself the prisoner of his publisher.

Even when Dekermore’s gender is known to both Stradelli and to Verne, she refuses any sparing of the labors of the journey in deference to her womanhood, insisting on carrying on as she had when impersonating a man. When Verne has an attack of diabetes, Dekermore and Stradelli mistake his prophetic visions for the future of Venezuela as nothing more than delirium.

Verne answers Dekermore’s question about Honorine by explaining that she could not live the artists’s life. He asks Dekermore if she loves him or “Jules Verne,” which he indicates are two distinct entities, which she fails to comprehend. When the younger duo ascend a mountain and Verne is physically unable to follow them, he sees them kissing at its summit. They surprise him upon their return not by declaring their love but that they will go to the mission, believing it, the gold, and the source of the Orinoco are all at one and the same place. Verne knows that youth has called to youth, and will join a band of Indians for the return. He is already converting his experience into prose in his journal.

The conclusion is much abbreviated as the movie winds up its 95 minutes. Arriving at the mission, of course the padre there is Dekermore’s father. 1888–EL EXTRAORDINARIO VIAJE DE JULES VERNE does not even offer an explanation; it is simply the “happy ending” the audience is expected to know will be the outcome. Stradelli plants an Italian flag, for a stream near the mission is indeed the source of the Orinoco, not the one found by the Frenchman. But who will be able to prove it?

For 1888–EL EXTRAORDINARIO VIAJE DE JULES VERNE, womanhood becomes even more indeterminate than in the novel. Dekermore never settles into feminine garb; while in the red dress once she has found her father, and in which she had introduced herself to Verne before their affair began, while with Stradelli discovering the source of the Orinoco she is once again in pants and male garb suited to exploration.

In the final shot, 1888–EL EXTRAORDINARIO VIAJE DE JULES VERNE comes full circle. Verne is alone, back at the wheel of his yacht Saint-Michel III–a plate commemorating it had been smashed by Honorine in the opening scene. Verne is a free spirit, a romantic and a man of nature, an inspiration, but it is left to the geographer to fully map the unknown areas of the landscape and the human heart.

1888–EL EXTRAORDINARIO VIAJE DE JULES VERNE not only emerges from the Spanish-language tradition of Verne filmmaking, but also reveals new possibilities for referentiality, especially in bringing Verne himself to the screen as a character. (I am considering fictional, not documentary, renderings of Verne on the screen here). The conception of Verne as character and writer is wholly different from previous films. In the 1926 French version of MICHEL STROGOFF, an opening scene had showed the writer at his desk composing the novel. Verne took a rather more active role in FROM THE EARTH TO THE MOON (1958), but as “J.V.,” a supporting character whose identity is revealed in the last scene to reveal a “twist ending.” In attempting to assert the triumph of imagination over science, his introduction serves to distract from a muddled conclusion. This portrait is akin to a “real,” not imagined person, unlike the young Verne portrayed in the science fiction television series THE SECRET ADVENTURES OF JULES VERNE (2000). Similarly, the Verne played by Michel Piccolini opposite H.G. Wells and a panoply of individuals of the past in the 18 minute film TIMEKEEPER/ FROM TIME TO TIME / LE VISIONARIUM, shown at various Disney theme parks in the 1990s, was to create a legendary figure, the familiar prophet of the future. THE HALLMARK THEATER: OUT OF JULES VERNE (NBC television, 1954) presented a half hour biographical dramatization of the young writer interacting with Honorine, Félix Nadar, and Hetzel.

1888–EL EXTRAORDINARIO VIAJE DE JULES VERNE, however, unlike all of these, actually makes Verne part of his own text. It does not do so in the faux manner of THE SECRET ADVENTURES OF JULES VERNE, involving him with the characters of Phileas Fogg and Passepartout in exploits that could not be further from those Verne imagined. Underlying that series was the suggestion that it was these experiences which inspired the writer. By contrast, 1888–EL EXTRAORDINARIO VIAJE DE JULES VERNE persuasively involves Verne in the creation of his own narrative, tapping the sources of inspiration, of love, and of identity. Here is a notion of the writer which this time may be lauded, a truly ingenious interpretation but one nonetheless compatible with the novel that inspired it.